Today, I’d like to share a simple lesson that’s served me well. It’s applicable not only to Magic and game design, but basically any situation where someone asks for an opinion.

Let’s talk about providing actionable feedback. We’ll begin, unusually for Drawing Live, with a story.

Growing up, I wrote lots of essays. History papers, literary commentary, bible studies, science biographies. I had the luxury of attentive parents and a father who delighted in reading, editing, and critiquing his children’s work. Our mother would happily go over what we wrote with us, but our father would hop into Microsoft Word, flip on Track Changes, and cover our papers in digital red ink. He’d flag typos and grammatical errors, of course, but he’d also point out weak phrasing, unfounded jumps in logic, paragraphs unrelated to our theses, and that our stated thesis might not be what we really intended to argue. After an hour or two of implementing his changes, we’d have excellent papers.

As I grew older, this continued. I was terrified of the college application process, and while yes, I did write all of my essays, I was secure in the knowledge that (as long as I got them done in time to receive and incorporate any edits) they’d be good. Then, I went off to college. I could email my father my papers, but after a time, I stopped. I’d become a more confident writer. Maybe I wanted a bit of distance from my father, particularly since I was attending his alma mater. And I definitely didn’t want to commit to doing my work early enough to get critique. So, if I wanted any digital red ink on my papers, I had to put it there myself (or ask a friend, but I can’t recall ever asking for help—I wasn’t very good at it at that age).

At the end of my sophomore year, I took the signature class of Union College: The Holocaust. Yes, it’s really called that. It’s been taught by the same professor since my father went to Union. It’s one of the only classes taught in a large lecture hall (Union’s a small liberal arts college) and is notorious for being difficult. One’s supposed to take The Holocaust pass-fail in their senior year. Well, I took it for credit as a sophomore. I’d also not taken a history class since junior year of high school and was never very good at the subject, so I wasn’t setting myself up for success. The class was graded on only two assignments: an in-class exam and a pair of ten page essays (which provided the majority of the grade). I did well enough on the exam, hopped on the train back to New York, and wrote the essays at my parents’ place. I gave them to my happy father. He got to work, and then told me they were terrible. I needed to completely rewrite one of them.

I didn’t want to hear that. Sure, I had another day or two before they were due, but I was done. I ignored his critiques and submitted my paper.

The average grade in that class was something like a C-. To the best of my knowledge, only one person got an A that year. That person was my friend, Rachel. But! I got an A-, which ain’t shabby.

The realization I had that day is that my father, while well-intentioned, didn’t give me the feedback I wanted. I knew what the professor wanted. He wanted a substantial regurgitation of the course material with some opinion put in, not twenty pages of opinion. Looking back, he was one man with a classroom of emotionally overwhelmed students, maybe one TA, and something like two thousand pages of essay to grade in the span of a few weeks—his goal was making sure his students had internalized what he’d said. The class didn’t teach the kind of scrutiny my father wanted to be in my paper, so it wasn’t going to evaluate its students based on skills it didn’t transmit.

There were two failures that day. Yes, my father failed to give me the feedback I wanted, but I’d failed to tell him what feedback I needed. I was looking for proofreading and only that, but he was accustomed to me asking for critique.

To receive good feedback, you need to tell the other person what kind of feedback you’re looking to receive. To give good feedback, you must first know what to focus on. When you match feedback with what it’s needed for, you have actionable feedback: feedback that actually benefits the recipient.

When I sit down and playtest another designer’s prototype, I want to know what stage of readiness the product is in. If it’s an early prototype and they’re still figuring out what it is, giving them feedback on systems balance and proofreading their rules is pretty useless—they want to know how and whether the mechanics are working, what’s fun, and what will get them to their next prototype. That other stuff will come later. A game that’s close to production, however, needs the exact opposite—there isn’t much that they can change, so rules proofreading and minor bits of balance are all they can act upon. Critiquing their mechanics or suggesting they take the game in a wildly different direction can be less than useless—you might undermine their confidence in the game. Unfortunately, I see this all too often, where designers focus on what matters to them, or show off how they’d do it, when that’s neither what the other person wants nor needs to hear.

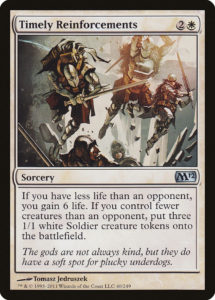

So, how does this apply to Magic? Well, it’s simple. If someone asks you for advice, clarify the bounds of what advice is or is not helpful. If someone wants to build a budget Modern burn deck for under $100, telling them, “You really should buy a playset of Arid Mesas,” is unhelpful and beyond the parameters. Telling them about trading (possibly up to an Arid Mesa) might not be, and maybe telling them about some lesser played but still playable cards (like Bump in the Night, Lightning Strike, or Ghitu Lavarunner can help them. If someone asks me about building a competitive EDH deck, I know that I simply can’t help them, as competitive Commander is not something I know about. But, I do know a bunch of obscure cards. If that’s within the bounds of their interest, I can help with that.

When someone asks me what they can do to be better at Magic, it’s very easy to tell them what I’ve done that I think makes me better. It’s more important to ask them what being better at Magic means to them. To me, it’s about tight play and being good at Limited, but to them, success could be about being good at Standard, or deckbuilding, or custom card design, or judging, or enjoying themselves. The best answers come from a thorough understanding of what questions they’re answering. This realization has made me not only a better Magic player and game designer, but a better and more empathetic person. I heartily recommend it, and I’ve gotten some good feedback about it, too.

And, as always, thanks for reading.

—Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic.

His favorite card of the month is Prophetic Prism, which is also his favorite design of all time. It’s a simple but powerful effect in Limited, allowing ambitious manabases while having nice synergies with mechanics like Improvise and sacrifice effects. Also, it always has absolutely gorgeous art.