Cover Image: Urza’s Guilt by Paolo Parente

1994’s Antiquities told the story of the battle between dueling archeologists and brothers Urza and Mishra, from their destruction of Argoth to Mishra’s seduction by Phyrexia. As an 85-card set, though, it was trying to pack too much into too few cards. The set was also plagued by early Magic design choices, like the comically underpowered Dragon Engine and comically overpowered Mishra’s Workshop and Candelabra of Tawnos. The Brothers’ War is the inciting incident for much of Magic’s history—it’s the cause of the Ice Age, the genesis of the Weatherlight Saga, and the path that leads to the Phyrexian invasions of Dominaria and Mirrodin—but it was given pretty short shrift in Antiquities.

Now, at the end of 2022, we’re retelling the story of the brothers at the scale it deserves: with literally larger-than-life protagonists and a fuller view of the conflict, including the role of the Fallaji and the Thran and, most especially, the Third Path. The Dragon Engines may still be weirdly small (Phyrexian Dragon Engine), but otherwise, the set feels like its expanding the scale of one of Magic’s earliest sets without being redundant, a revision without repetition.

From a mechanical standpoint, though, The Brothers’ War feels most like Rise of the Eldrazi. I doubt too many current players recall that decade-past set, but Limited was incredibly fun. You could draft a Defender deck and burn your opponent out of the game with Vent Sentinel; you could draft expendable creatures and Raid Bombardments to win while your opponent was still trying to ramp up to their Ulamog’s Crusher; you could pivot to Broodwarden and Spawn tribal; or you could cash in those same Spawn tokens to make enormous Eldrazi.

In The Brothers’ War, we have massive Dreadnoughts and titanic Constructs in place of Eldrazi. Powerstones serve as more permanent Spawn tokens for building up to your eight drops and the various Prototype haymakers are flexible cards along the curve, fixing part of the stagnation from Rise. I’m pretty taken with the mechanic: with Prototype, you can adapt your creature to different stages of the game, with Phyrexian Fleshgorger operating in the majority of games as a particularly gnarly three-drop with the option to, in a game that’s gone on long enough, close out as a massive threat.

Hand of Emrakul was a favorite of mine, because it was surprisingly easy to pull off the alternate cost—and surprisingly easy to hit seven mana in the format, so you were set either way. Prototype, as printed in The Brothers’ War, feels similar: you’re never unhappy with the creature it produces, whether you can cast it for the full mana value or at the discount price.

Aside from fleshing out the war machines that the brothers employed in their struggle, the expanded space of The Brothers’ War means the major participants are given more room to develop. Antiquities came at an odd time in Magic’s history—pre-Legends, there was no way to depict unique characters. Arabian Nights tried, with characters like Ali from Cairo and Aladdin printed as though they were cannon fodder like your regular Soldiers and Birds. Antiquities didn’t even try to depict Mishra, Urza, Ashnod, Gix, Tawnos, Tocasia, or Kayla, although the little-loved Vanguard cards from a few years later would go on to attempt to capture these mythical figures.

I’m glad Wizards waited until they were able to do the participants justice—with Urza, Mishra, and Titania as Meld cards, and several versions of each brother between the main set and ancillary products, The Brothers’ War provides a more exciting (and playable) version of each character than we were likely to get back at the game’s inception. Through these cycles and their effects, we see hints at the philosophy and magical praxis that doomed each character.

In the story, Mishra loses his humanity directly: he is corrupted by Phyrexia, merges his flesh with machine, renounces his connection to his birth race. His final fate is unclear—Urza finds what appears to be Mishra in his explorations of Phyrexia post-Invasion (Urza’s Guilt), but there’s no confirmation as to whether he finds Mishra, a ruse of Yawgmoth’s, or a hallucination brought on by his own instability. Whatever Urza found down in the bowels of Phyrexia, Mishra was lost to Urza long ago. He is a willing collaborator to Phyrexia and treats humans as disposable at best or as walking organ farms.

Urza loses his humanity more subtly but just as completely. While he defends humanity (and goblinhood, and merfolkship, etc.) against its extinction, he has eschewed any relationship or human connection. He marries into wealth to convert it to artifice, wages war against his brother over a couple of highfalutin batteries, and eventually alienates his greatest allies, Barrin and Teferi.

Urza extracts whatever is useful from a relationship and then junks the husk. He is more than willing to despoil nature in the service of harvesting resources for his war effort, as we see in cards like Cradle Clearcutter, and his eugenics project and detonation of the Sylex still affect “modern” Dominaria and the multiverse. Part Oppenheimer without the quotability, part Stalin without the charisma, part Westmoreland with even less interest in human costs; Urza will do anything to preserve Dominaria from Phyrexia, even if the only thing left to preserve is a smoking, unpopulated crater.

Tawnos, Urza’s apprentice, is a gentle foil. Where Ashnod dissects humans for inspiration, Tawnos observes nature and replicates its designs in his work (initially as a toymaker, and then as a weapons manufacturer). His creations were geared towards mitigation—resilient Clay Statues and recurring Clay Revenants. Notably, though, his greatest creation, which ends up saving him from the detonation of the Sylex, was The Stasis Coffin, originally intended for Mishra. The plan was to permanently imprison Mishra in the coffin, trapping him without hope of escape, but Urza’s detonation of the Sylex obviated that plan, and Tawnos used his own creation to survive the blast.

Ashnod, Mishra’s second-in-command, is interested primarily in other humans as raw materials. She turns the corpses of soldiers into necromantic automatons and vivisects the living to learn more about how to further her craft. She’s a useful ally to Phyrexia simply because her methods and modus operandi align with the hell plane’s—while she eventually grows uncomfortable with Mishra’s inhumanity and sabotages him by providing the Golgothian Sylex to Tawnos, her transmogrant troops and cruel tactics were vital assets to the Mishran war effort. Notably, Ashnod atones, somehow surviving the blast and eventually winding up as Tawnos’ partner and co-founder of the Conclave of Mages. A torturer, war criminal, and practitioner of human sacrifice, she is still depicted as redeemable.

The most interesting aspect of our revisit of this storyline-defining event in Dominarian history, a function of having more space and context, is that we’re able to see how the war affects those directly involved in its struggles. While Urza and Mishra are focused predominantly on creating and deploying war engines of titanic scale, the Brothers’ War was still a ground war relying on troop action. In The Brothers’ War, we see these troops in the literal trenches, trying, with a layperson’s experiences, to come to terms with the toll the war has taken on their lives and the entirety of Dominaria.

In cards like In the Trenches, Repair and Recharge, and Conscripted Infantry, we see the disposability and expendability of the human troops drafted or compelled into the brothers’ war. For years, we’ve been told about the effects of the War on the macro- scale—the Ice Age, the time rifts, the protective sealing away of Dominaria—but we truly see the micro- scale with this set. When wizards of godlike power clash, it’s not just the temporal and spatial fabric that gets rent, but the societal tapestry as well.

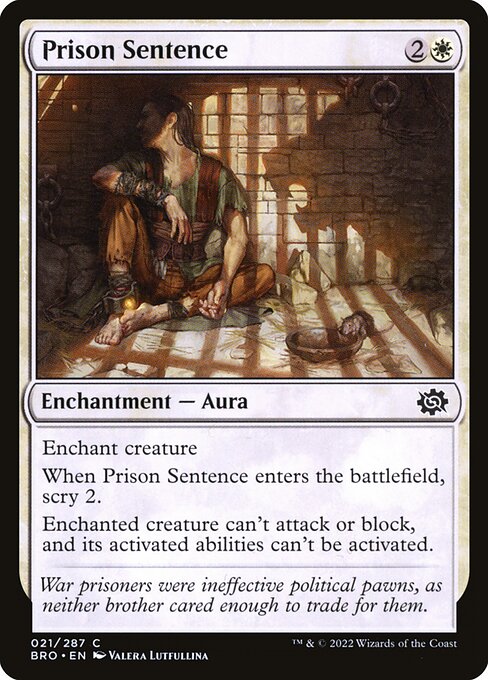

Mark Rosewater is on record as saying that if a set’s theme isn’t present at common, then it isn’t truly a set’s theme. He’s speaking mechanically, but I think he would agree that axiom holds true for philosophical themes, as well. The Brothers’ War theme is best expressed in a humble (albeit exceptional) Limited card: Prison Sentence. Urza and Mishra may be ideologically opposed, but the flavor text displays that the two warring brothers have something in common: a disinterest in humanity.

Prison Sentence is Arrest with an added Scry 2—Scrying, of course, represents the acquisition of or search for knowledge within the text of Magic, leading us to ask: what are we doing to the prisoner to get that knowledge? The Geneva Convention defines the governance and care of prisoners of war, rules which don’t apply to historical Dominaria conflict, but are nevertheless flaunted by Urza and Mishra. To me, this is among the darkest pieces of flavor text in Magic, implying we’re just as wrong to root for Urza as we would be to root for Mishra.

Confining humans without the hope of release is barbaric, and that was at the core of Urza’s plan and collateral damage to both armies. Mishra’s Phyrexian allies (and eventual masters) sought the destruction and compleation of all life; Urza sought to preserve his preferred subsection of all life. In the service of their goals, they stripped the land of its resources, slaughtered and conscripted thousands of civilians, and left war machines to litter the landscape and pollute entire habitats. The lessons they learned as artificers became cruelly ironic; rather than preserve the past, as they were taught by Tocasia, they destroyed the future of Dominaria in the name of industry. At the start of the 21st century, with the data we have about humankind’s impact on our world, it’s a stark lesson.

Capitalism extracts. That is its sole purpose. Any advances in technology or extensions in lifespans are side benefits—a way to keep the labor force functioning and exploitable. The purpose of capitalism is to extract resources from our world and labor from our communities and then sell us the products we ourselves made at a markup, whether that’s coal or cars or cards. We, the Magic players, have instilled the game with value, through our love of the game and the legends we built around our experience with the game pieces. Every veteran player who shows a newer player a Mox or a shockland, walks them through why it’s good, is, on a microscopic level, being a brand evangelist for Wizards of the Coast.

I am a brand evangelist for Magic. I believe it’s the second best game humanity has invented and I intend to spend the rest of my life playing it and teaching others to play it. But Magic, as a cultural product developed under capitalism, takes on the characteristics of its environment. I’m not innocent here: you’ll notice I’m comfortable with the phrase “brand evangelist” rather than demanding the label of “game evangelist.” Magic’s brand is shifting here as capitalism mutates it into a kind of mega-amalgamation and crossover consolidation tactic—it’s become willing to open up to other intellectual properties, with mixed results—but the brand is strong.

I can’t think of any other company that publishes its psychographic information and lets players characterize themselves along those axes—“Oh, I’m Johnny all the way!” or “Proud to be an Izzet mage” is a Wizards-defined, player-applied label, and those are the ones that stick best. By giving us, the players, access to identity modifiers that wouldn’t generally leave the boardroom, Wizards offers us a sense (or an illusion if you want to be cynical) of trust. Metaphorically, we’re those soldiers in the trenches, looking up at titans warring over territory and resources, but we feel in control of the situation because we have a handy name to apply to ourselves, to give us a sense of belonging.

We don’t just consume Magic; we champion it. As we enter Magic’s thirtieth year, and as we revisit how it started, it’s worth seeing with clear eyes who we’re following into battle, and what territory we hope to claim—and what will be left once we achieve our goals.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.