Planeswalkers have held signature roles in the story of Magic: the Gathering for decades. Long before Lorwyn brought planeswalkers to the game, and long before War of the Spark put them front-and-center, planeswalkers were defining the dramatic arcs of Magic lore.

Many discovered Urza and his ascension to planeswalker status in 1998 with the release of the Urza’s Saga set and the Planeswalker novel by Lynn Abbey. Even before then, some read the Jared Carthalion comics or the Harper Prism books featuring Greensleeves. What ties each of these pre-Mending planeswalkers together—and unites them with the protagonists of the Magic story today—is the mystical, unfathomable planeswalker spark.

The spark has gone through a few iterations to reach its current form. It seems only right that we take time now, with the release of War of the Spark, to look back at the spark through the ages of Magic—to understand it, its functions and limitations, and its role in Magic Story today.

Basic lands panorama from War of the Spark. Art by Richard Wright.

My Heart of Gold: The Pre-Revisionist Era

It’s important to note that the further back we go into Magic lore, the concepts presented become less refined.

While that may seem like a “no duh” kind of acknowledgement, it’s important to recognize that early Vorthos aspects look like mere chicken-scratch notes on a cocktail napkin when compared to where we are today. You can either look at these conflicting pieces of information between eras of story design as contradictions and inaccuracies, or you can imagine that the characters in-universe have learned more over time about the Multiverse’s heady metaphysical concepts—just like us.

A perfect example of this is the dilemma with Greensleeves—a human druid from Dominaria, a protagonist of three early Magic novels, and apparently the first character we ever see learn to planeswalk.

Sole depiction of Greensleeves. Crop of “Giant Badger.” Art by Liz Danforth.

However, not one of these novels (Whispering Woods, Shattered Chains, and Final Sacrifice) ever shows her actually ascending to planeswalker status. In fact, her unreliable narrator of a mentor describes planeswalking as just another form of using magic, albeit a much higher-level form. Berend Boer, in his blog “Multiverse in Review,” gives the clearest description of what early Magic stories said it took to ascend to planeswalker status:

Everyone in [Arena] assumes you just become [a planeswalker] when you gather enough mana…. You’d think that after ascension planeswalkers would realize the true nature of the spark, but I guess not.

In this era of Magic storytelling, just scoop up as much mana as you can and squish it into your soul and POOF: instant planeswalker. The easiest way to reconcile this with our current understanding of the Multiverse is to say that characters such as Greensleeves, Kuthuman (the antagonist of Arena), and Greensleeves’s druidic mentor Chaney all had latent Sparks that happened to be flared by the major spells we see them employ—though Boer posits a different theory to explain away these continuity errors.

Supposedly any mortal mage was able to study the ways of the planeswalker and, given enough time, can learn to travel from world to world. This means that, back in the mid-1990’s, the spark didn’t even really exist.

We Looked Like Giants: The Pre-Mending Era

In the real world, three years pass before anything significant changes regarding planeswalkers. In-universe for the story, we actually go back just over 4,000 years to the end of The Brothers’ War, which Urza ended by activating the Golgothian Sylex – an artifact whose magical explosion flared Urza’s latent spark and turned him into a planeswalker.

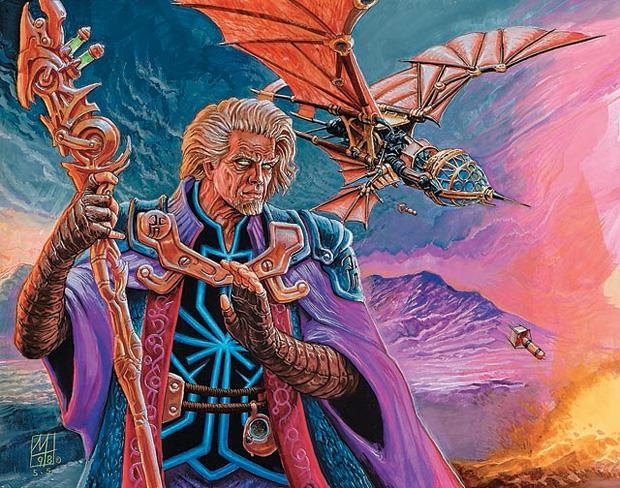

Crop of “Urza Vanguard card.” Art by Mark Tedin.

In the Artifacts Cycle of novels, Magic Story began to clarify what it meant to be a planeswalker, and that began with an actual concept of a spark and ended with nearly unlimited power. A being had to have a not-yet-active magical potential tied to their soul (the spark) in order to eventually become a planeswalker, though there were rare occurrences where sparks could be transferred to another person or object. Glacian’s latent spark was trapped in what would become the Mightstone and Weakstone, and Karn ascended due to Urza and Glacian’s sparks melding with him as the Legacy Weapon erupted.

Listing the things that planeswalkers in this era couldn’t do might actually be easier than defining what they could. “Oldwalkers,” as they are now known, had bodies that were merely projections of their minds and could alter them at will—changing their appearance, species, whether or not they were solid or intangible. In fact, in moments of deep thought (or mild insanity) Urza would forget to keep his body materially composed. From Lynn Abbey’s Planeswalker novel:

Urza spun quickly on the stool, too quickly for her eyes to follow his movement. Indeed, he hadn’t moved, he’d reshaped himself. It was never a good sign when Urza forgot his body.

Urza often forgot to eat (he didn’t need to), and early on in his ascended days he often forgot his mortal companions needed food, rest, and—you know—air to breathe.

Oh, and they were all immortal. Literally. In a duel at the Madaran rift during the Time Spiral novel, Nicol Bolas shreds Teferi’s body and leaves him as only a head, which then has to rebuild his body. Similarly, when he was beheaded during the Apocalypse novel, Urza remained alive (though Yawgmoth’s power left him unable to reincorporate himself fully). As long as a planeswalker’s mind was undamaged, they remained alive.

Later on, Karn had enough power to create his own artificial plane—the metallic and mathematically perfect Mirrodin. While an extremely powerful mortal wizard could reshape parts of a landscape, or control elements around them, few beings other than pre-Mending planeswalkers had the magnitude of power to actually shape or create an entire world. Other examples of this include Bolas altering the magical structure of the entire plane of Amonkhet, Commodore Guff literally and figuratively changing history by erasing the end of his “Dominarian Apocalypse” storybook, and Teferi phasing out a whole continent on Dominaria.

Though “we were gods once” is a fairly common meme these days in Vorthos circles, that doesn’t make it any less true back then.

Everything Has Changed: The Post-Mending Era

In the wake of cataclysm after cataclysm, Dominaria’s space-time fabric was rent and collapsing. These time rifts had resulted from major spell and artifact uses in history and were directly linked to the sparks of planeswalkers. In order to seal these rifts, oldwalkers like Freyalise, Lord Windgrace, and Jeska (among others) had to sacrifice their sparks (and sometimes lives) and the result was not only saving the Multiverse, but fundamentally altering the way the planeswalker spark functioned.

“Retether” from Planar Chaos. Art by Dan Scott.

With this event, certain limits to powers were discovered for both “neowalkers” and previously god-like planeswalkers. No longer were planeswalkers immortal or invincible; they lived and died like every other being in the Multiverse. They could no longer transport organic beings with them across the Blind Eternities (the void between worlds), as the spark’s protection from the magical chaos wasn’t powerful enough any longer to extend past its user’s own body. Their bodies were no longer mental projections but simple flesh-and-blood (or whatever they were born/created with) that couldn’t be altered at will.

Finally, and this will become even more important in the last segment, not just any planeswalker could hoard gobs of mana within themselves or use mana from planes other than the one they were on. This meant that spells requiring vast amounts of mana were restrained by both the magical potential of the individual’s spark and training and the environment they were in. Even the most ancient and powerful planeswalkers, therefore, had their limitations now.

And that didn’t sit well with all of them.

Shimmering Neon Lights: War of the Spark

Finally we arrive at the present day on Ravnica, where Nicol Bolas enacts his grand scheme centuries in the making: to unleash an ancient ritual, the Elderspell, and harvest the sparks of thousands of other planeswalkers in an attempt to regain his immortality and power potential from before the Mending.

Crop of “Nicol Bolas, Dragon-God” from War of the Spark. Art by Raymond Swanland.

Not much about the metaphysics of the spark changes in this story, but it is given its first visual representation ever. The art above shows harvested sparks swirling around Bolas, while art for the cards Despark, Spark Harvest, The Elderspell, Richard Wright’s basic lands panorama (shown at the top of this article), and the set teaser trailer also illuminate the physical form of a planeswalker’s power.

The glowing blue-white energy aesthetic of these sparks also seems to reinforce the theory that Kelly Digges and Ethan Fleischer discussed in internal Wizards of the Coast documents that the spark is a “birthmark” of aether (the same substance that makes up the Blind Eternities) left on a being’s soul as its life begins, thus tying the nature of the spark even tighter into the very nature of the Multiverse itself.

One of the greatest metaphysical mysteries of Magic: the Gathering, the spark that makes mortals into planeswalkers and gives them incredible powers may never be fully understood. But, like the mysteries of our own human potential and the possible existence of the soul, perhaps that wonder is necessary to keep us searching and seeking to learn more about the Multiverse around us.

Joe Redemann is a Vorthos writer for HOTC, specializing in Magic Story and lore. He seeks to connect the stories of the Multiverse to our own daily lives, exploring social issues and philosophical questions through the lens of Magic in both his writing and podcast, Goblin Lore.