Ahoy planeswalkers! Before I dive into my article this week, I need to give a little background on myself. For the last five years, I have been working on a Ph.D. in theater history. One of my chief scholarly interests is the theater of Spain’s Siglo de Oro—the Golden Age (literally the Century of Gold), spanning roughly the early 1500s to the late 1600s, when the Spanish Empire was at its peak. My interest in this period as a scholar has given me a little more knowledge of the era’s history and culture than the average Magic player, and the ways in which the history has been translated into Ixalan fascinates me. I’d like to write a little bit today about a couple of specific subtopics that may have influenced the creation of the world of Ixalan and at least one of its major characters: the Reconquista, Limpieza de Sangre, and Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz.

The Dusk Legion, The Reconquista, and Spanish Golden Age Society

The way the Dusk Legion’s invasion of Ixalan mimics Spanish colonialism in the Americas has gotten a lot of attention, but I’m really enjoying tracing how the Dusk Legion’s conquest of Torrezon echoes the real-life ascension of Spain’s Christian kingdoms. So, here’s what we know about the Dusk Legion’s home continent. They began their efforts to conquer Torrezon about 700-800 years ago, and completed their conquest a little over 50 years ago, per this week’s story. The pirates’ ancestors fled around that same time, some non-vampire residents remain, and they seem to have a strongly hierarchical society ruled by a queen.

The timeline of the Dusk Legion’s conquest of Torrezon strongly mirrors the history of the Reconquista in Spain, which spans just shy of 800 years, from the Moors completing their conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 to the fall of Grenada in 1492 (notably, the same year that Christopher Columbus took to the sea). Following their victories, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel established Catholicism as the state religion, and the Spanish Inquisition was established to ensure compliance. Under the Inquisition, Spain’s Jews and Muslims, who had coexisted with the peninsula’s Catholics for centuries, had to choose between converting or facing the risk of deportation, torture, and death.

The strong entwining of religion and state is quite overt in Wednesday’s “The Race, Part 1” and in the flavor text of cards like Bishop’s Soldier. Among the more intriguing parallels with the establishment of Spain’s state religion comes when Vona, Butcher of Magan feeds upon a pirate for rejecting the Queen’s sovereignty. On one hand Vona is also secretly somewhat heretical in how thoroughly she has embraced her vampirism and may have just been looking for an excuse; but on the other hand, cards like Bishop of the Bloodstained suggest that this is an orthodox position.

So, there is a viable parallel here: the expectation of the Dusk Legion’s vampires is that their mortal subjects convert to their state religion, and failing to do so is grounds for becoming vampire food. Clearly, as I alluded to a little bit in my set review, many humans have pledged loyalty to the Dusk Legion. The way the set subtly frames that choice as “convert or die,” however, casts this dynamic in a new light that filters through another episode of genocidal violence from Western history.

Limpieza de Sangre

Following the Reconquista and the first wave of the Spanish Inquisition, over the next couple of centuries, Spanish society developed a growing obsession with what was called limpieza de sangre—literally “cleanness of blood,” although “blood purity” is probably a better translation. By this time, at least officially, there were no more Jews or Muslims in Spain; they had converted, been expelled, or been killed as heretics. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, however, even having converted was not enough: the families of conversos (converted Jews) and moriscos (converted Muslims) were also subject to expulsion. Since mixed ancestry was not necessarily something that could be detected by sight, knowledge of one’s lineage became vital to demonstrating one’s social worthiness, especially among the noble classes.

This history echoes within Ixalan’s on-card storytelling a in few ways. John Dale Beety has made a good case that Wizards has crossed a line in its transposition of Catholicism into the blood-centric religion of the Dusk Legion, and this is certainly the connection more players will be able to immediately draw. But an obsession with blood (as a stand-in for ancestry) is also highly typical of Spanish society during the heyday of its empire. The obsession with blood that this faction has does not solely derive from the Catholicism of their real-world analogues; it was also interwoven into the social power dynamics with almost a level of paranoia.

Considering limpieza de sangre also helps us get a little more at the clear second-class citizenship here that creeps into the gameplay even—Seekers’ Squire is Dusk Legion-aligned, but she is not going to interact with your vampire synergies. The reprinted Mark of the Vampire suggests faithful service can earn social advancement to becoming a vampire, but it seems likely that even then one would struggle to advance beyond the lowest class of vampires. Legion’s Judgment suggests that the Dusk Legion shares their real-world analogues’ obsession with history, while “The Race, Part 1” reveals the reverence for the earliest converts to the Church of Dusk through the character of Mavren Fein, Dusk Apostle.

Huatli, Warrior Poet and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Huatli is a particularly fascinating character with regard to her real-life referentiality. The idea of her as a warrior-poet seems designed to draw upon Aztec history, as the Sun Empire’s design does on a larger scale. So, she delivers this poetic oration in Magic Story:

A look at some of the surviving Aztec poetry reveals the style at work here. It’s a pretty good fantasy mirror to its most obvious real-life counterpart. So far, so good. Where this analysis becomes complicated, however, is in Huatli’s flavor text, which does not always jive with this poetic form.

Rallying Roar and Slash of Talons fit with the style of Huatli’s poem in Magic Story, with their themes of national pride and martial power and their punchy cadence.

Kinjalli’s Sunwing, Favorable Winds, and Lurking Chupacabra, however, all point in a different direction. They abandon these themes in favor of natural subjects. There is a marked weight to the language, combined with a somewhat meandering sentence structure that differs from the punchy lines of the Aztec poetry. Baroque, I might be tempted to call it. And thinking about baroque woman poets of American indigenous ancestry makes me think about a specific poet: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

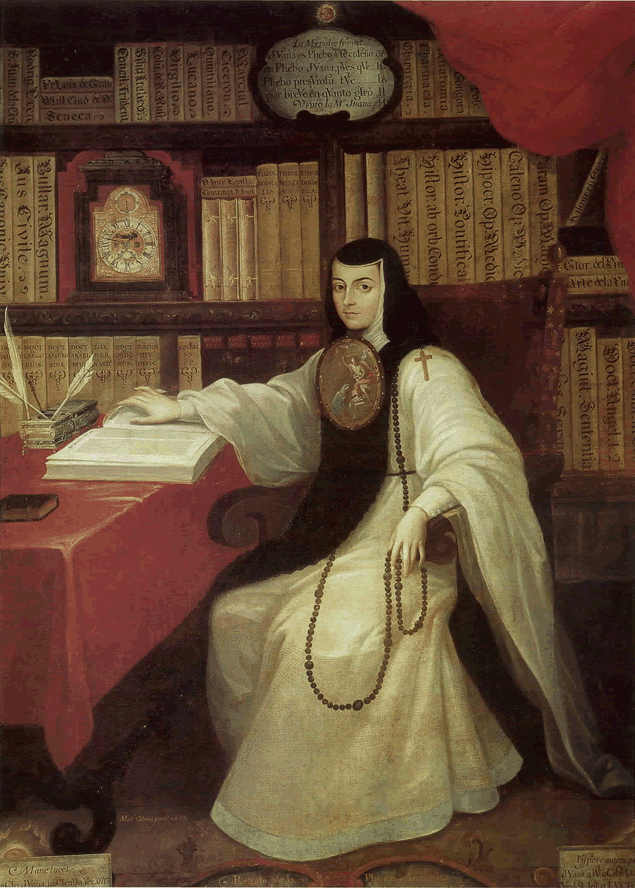

Sor Juana was born in New Spain (Mexico) of mixed ancestry—her father was a Spaniard, her mother at least partially of indigenous ancestry. A remarkably brilliant woman in a society that did not particularly prize such gifts; she became a nun, acquired an impressive library, and became a prominent figure in the intellectual life of Mexico City. Her plays and poetry have survived, and her stature is such that she is now depicted on Mexico’s currency.

Sor Juana was at her peak of productivity in the later part of the 1600s, towards the end of Spain’s Siglo de Oro. Significantly, she was writing within an intellectual context in which poets like Pedro Calderón de la Barca were celebrated, and Sor Juana’s poetry and playwriting were in conversation with the works of these top male playwrights, both from the Spanish mainland and at home in Mexico.

Now, I should probably use some of Sor Juana’s poetry here, but I know Calderón better than I know Sor Juana—I translated one of Calderón’s plays as part of my MFA—and what I’m really trying to get at is the era’s poetic style. The flavor texts for Kinjalli’s Sunwing, Favorable Winds, and Lurking Chupacabra scream Spanish Golden Age to me. If you’ll forgive my vanity in this, compare them with this passage from my translation of Calderón’s play Life is a Dream:

This might be just me, but this is what Huatli’s flavor text makes me think about: the meandering sentence structure, the picturesque yet weighty language, the marked elegance and intensity. I strongly suspect that Magic has a flavor text writer with some knowledge of Spanish Golden Age poetry or drama. I don’t know if this was a directive from the top of Wizards—again, it doesn’t necessarily jive with Huatli’s poetic work in Magic Story thus far—but the linguistic approach of these flavor texts conjures the Spanish Golden Age. Connecting that with an Aztec-inspired woman planeswalker invites some connection with Sor Juana, one of Mexico’s most celebrated poets who happens to be partially of indigenous ancestry.

Thank you for joining me on this journey through Spanish and Mexican history! In two weeks on Scry Five: something a little lighter, as Halloween approaches!

Beck Holden is a Ph.D. student in theater who lives in the greater Boston area. He enjoys drafting, brewing for standard, and playing 8-Rack in modern. He also writes intermittently about actually playing Magic at beholdplaneswalker.wordpress.com.