Painting wasn’t always respected as a European fine art form, much less on top. Even in the Renaissance, source of the Mona Lisa and the Sistine Chapel ceiling among other masterpieces, Raphael made a series of large-scale preparatory works, now called the Raphael Cartoons, for execution in the then-pinnacle of two-dimensional art: tapestry.

“The Raphael Cartoons: Making the tapestries” by the Victoria and Albert Museum

Once painting gained respectability, however, its practitioners promptly began gatekeeping who could make it. France’s Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, founded in 1648, and its post-French Revolution successors, the Académie de peinture et de sculpture and Académie des Beaux-Arts, had a near-stranglehold on professional painting in that country. (Infamously, French authorities confiscated Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun‘s works and materials for practicing without Academy membership.) Similar Academies arose in various European countries, such as the United Kingdom’s Royal Academy of Arts.

The Hierarchy of Genres

In addition to deciding who could make art, the various Academies also dictated what was worth depicting. With minor variations across times and places, the Academic tier list of subjects, the “hierarchy of genres“, dictated which genres were held in esteem and which were considered lesser. The six major tiers, from most to least prestigious, were as follows:

- History painting (narratives of history, allegory, Christian faith, and ancient myth)

- Portraiture (identifiable people)

- Genre painting (scenes of daily life with “types” instead of individuals)

- Landscape (views of the countryside or urban environments)

- Animal painting (living animals)

- Still life (inanimate objects, to include dead animals)

While the hierarchy of genres had its artistic challengers from the mid-1800s and declined in tandem with the status of the Academies, the genres themselves have persisted wherever European-derived figurative art remains, such as illustration art. In fact, the art for Magic: The Gathering easily covers all six genres! Here’s how, starting from the bottom.

Still Life

Still life, the lowest genre in the hierarchy, depicts arrangements of objects, such as food, flowers, and dead animals such as birds or game. Because the Academies barred women from anatomy-drawing classes, even the few women who were full Academicians, specializing in still lifes was common for women painters of the time, such as flower painter Mary Moser RA.

As an action-oriented game, Magic: The Gathering doesn’t feature still life to excess, but it does have a notable share. Feast of the Unicorn is an early example, with the unicorn substituting for the usual boar’s head. The Food tokens of Throne of Eldraine and later sets are also primarily still lifes. Even flowers have their moment, as on Teachings of the Kirin.

Still lifes can also depict inorganic objects. In Magic: The Gathering, this shows up most prominently with artifacts, particularly Equipment. A fine recent example, highlighted in one of Donny Caltrider’s Grand Art Tours (as are all of the following large-art selections), is Hero’s Heirloom from Dominaria United, illustrated by Ovidio Cartagena. The Heirloom sword is not in the hands of a soldier but a statue, inspired by Bernini (per Cartagena on The Platform Formerly Known As Twitter). All is still; all is majestic. Cartagena’s work needs no hierarchy to validate it.

Hero’s Heirloom by Ovidio Cartagena. Digital.

Animal Painting

Moving from the dead to the living, next up is animal painting. The animals in question may be wild (foxes, boars, deer) or domesticated (horses, dogs, falcons). This genre was popular with wealthy private patrons, as many were sport hunters or animal breeders. The Marquess of Rockingham, for example, commissioned George Stubbs to paint his Thoroughbred stallion, Whistlejacket.

Magic: The Gathering abounds with creatures. On the domesticated side, there are surprisingly few horses, though The Lord of the Rings: Tales of Middle-earth offers Shadowfax, Lord of Horses. Tokens for domesticated animals such as goats and oxen abound, with Aaron Miller’s Ox token a lively example with just a hint of the fantastic. A fantasy spin on the domesticated animal painting is the depiction of animal familiars, such as the black cat on Cauldron Familiar.

On the wild side, Magic: The Gathering depicts creatures great and small. From the Grand Art Tour for recent release The Lost Caverns of Ixalan, Xolatoyac, the Smiling Flood is firmly on the “great” side, towering over the city it inundates. The axolotl smile and dusty-rose body set against a muted palette of blue-greens and yellows gives Xolatoyac a deceptively calm appearance at first glance, before the perspective kicks in and the cuteness turns terrifying.

Xolatoyac, the Smiling Flood by Campbell White. Digital.

Landscape

Landscape was well-established in the hierarchy of genres, and respectable, if not too respectable; the three genres depicting more than incidental human forms all rank higher. Landscapes and cityscapes range from the intricate detail of the real and imagined Venice scenes of Canaletto to the innovative light effects of J.M.W. Turner.

In Magic: The Gathering, the land card type created an immediate and obvious for landscapes from the beginning. John Avon became an iconic Magic artist through vibrant landscapes in airbrushed acrylic. Ann-Sophie de Steur’s Streets of New Capenna Mountain-as-skyscraper is not merely a basic land, but arguably the set’s defining image. Landscapes are not limited to land cards, either, as The Modern Age from Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty proves.

The Dominaria United Grand Art Tour reminded me of Thran Portal by Sarah Finnigan. In fewer than two dozen illustrations, she has already established herself as a powerhouse of landscape (indeed, all her cards through The Lost Caverns of Ixalan have been lands). Thran Portal uses a common theme of Academic landscapes, the ancient ruin, but with a fantasy twist: neither Greek nor Roman, the Thran structure is brimming with magical potential, yet utterly at home within the natural serenity surrounding it. A cultured youth on Dominaria’s equivalent of the Grand Tour surely would want such a painting as a souvenir of their travels!

Thran Portal by Sarah Finnigan, acrylic on wood, 18” x 24”

Genre Painting

Genre painting is the first of the “human” genres, depicting scenes of ordinary life. Subjects of notable genre paintings include domestic interiors, festivals, and sellers in the marketplace. Academic genre painting is almost always idealized; a key work in a timeline of the downfall of the Academy system, Gustave Courbet‘s The Stone Breakers, took a Realist approach to a genre painting subject and dared the Academy to say, “No, not like that.”

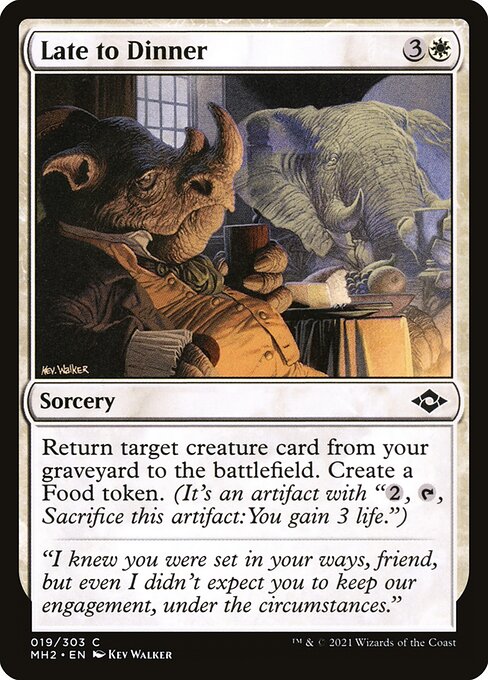

In The Lord of the Rings: Tales of Middle-earth and Tales of Middle-earth Commander, simple moments such as the toast on Banquet Guests heighten the stakes of other cards. The Sleight of Hand reprint in Wilds of Eldraine adds Faerie fun to a market scene. And while genre painting of the Academic era is often lighthearted or otherwise not seen as “serious”, Kev Walker’s Late to Dinner demonstrates its emotional potential.

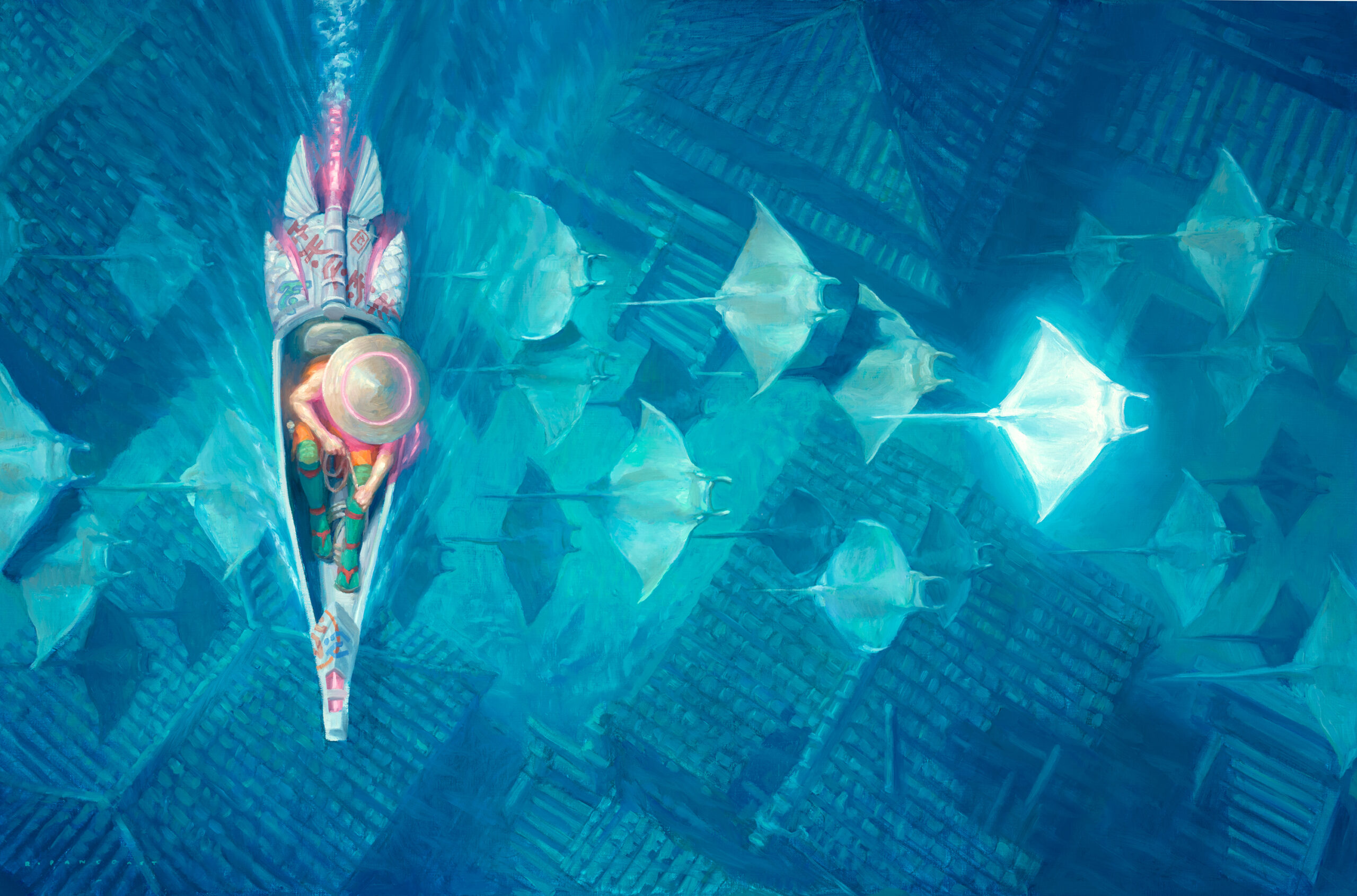

From the Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty Grand Art Tour, one of the best fantasy artworks of 2022 is a genre painting. Ryan Pancoast’s Discover the Impossible takes an unusual top-down view of a fisher on a boat, a classic genre painting subject in maritime areas, and sets this against the school of rays and the sunken structures beneath the clear water. The humble simplicity of the genre subject lets Pancoast’s technical mastery and innovation shine.

Discover the Impossible by Ryan Pancoast, oil on canvas, 20” x 30”

Portraiture

In portraiture, subjects go from unnamed types to recognizable individuals: nobles and royals, clerics and Popes, the odd wealthy merchant. Portraits under the Academy could be from the shoulders up, half-length (to the waist), to the knees, or full-length. They could be contemplative or active, with settings and props chosen to show their sitters at their most prestigious. Marie Antoinette, patron of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, posed for portraits alone and with her children.

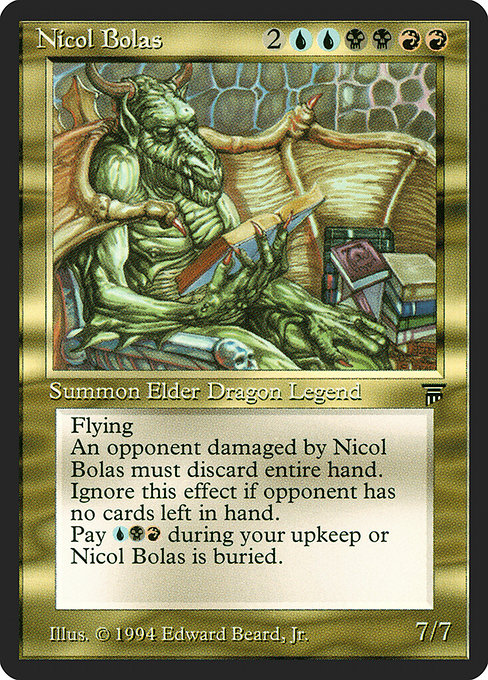

Portraiture in Magic: The Gathering arguably goes all the way back to Limited Edition Alpha. This becomes indisputable with the legendary creatures (to include sapient species beyond humans) of Legends, such as Nicol Bolas, one of the original Elder Dragons. Two portraits set on Innistrad, Winona Nelson’s Bruna, Light of Alabaster and Steve Argyle’s Thalia, Guardian of Thraben, show portraiture’s extremes of pulled-back and close-up perspective.

Starting with Lorwyn in 2007, planeswalkers have offered further portraiture opportunities. From the Innistrad: Crimson Vow Grand Art Tour, a recent highlight is Ekaterina Burmak’s Chandra, Dressed to Kill. This portrait of Chandra Nalaar in courtly finery, around three-quarters length as seen on cards, becomes even more special in isolation, where it becomes a glorious full-length portrait of the pyromancer as a vision in red.

Chandra, Dressed to Kill by Ekaterina Burmak. Digital.

History Painting

History painting, loftiest in the hierarchy of genres, depicts a scene from faith, myth, allegory, or the past. Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe, painted in 1770, made room in the genre for recent history. In the 1800s, however, history painting at its worst became an excuse to sell sex and violence by putting it in an “exotic” setting. The weakening of the Academies and the shift toward abstraction left history painting largely moribund in the fine arts.

By contrast, depicting scenes is one of Magic: The Gathering’s greatest needs. Instants and sorceries, such as Ryan Yee’s exquisite Die Young, are not permanent in either the regular or Magical sense, but moments chosen by the artist for a different sort of permanence. Ejiwa “Edge” Ebenebe’s version of Ponder, which shows Rielle, the Everwise nurturing a young woman’s gift, has the power of allegory. And Howard Lyon’s art for Sigarda’s Aid draws upon a long history of religious subjects, which he also paints.

In matching the grandeur of great history painting, however, few Magic illustrations can equal the leadoff from the March of the Machine Grand Art Tour, Storm the Seedcore, which depicts a moment in the Mirrans’ efforts to get the dryad Wrenn to Realmbreaker, the Invasion Tree. The work has a complex array of figures, yet the action is clear in a way Aaron Radney at Commander’s Herald saw as Neoclassical (the period when recent history joined history painting). Rainville himself has posted that Neoclassicism is one of many art-historical periods he has incorporated into his process, from the early Renaissance to 20th-century illustrator Norman Rockwell and the imaginative realism of Donato Giancola.

Storm the Seedcore by Jason Rainville. Digital

The Hierarchy You Climb…

The hierarchy of genres has not held sway for over half a century. After World War II, the Western art world’s center shifted from Europe to the United States, which had no national Academy, and Abstract Expressionism (which rejected the hierarchy’s contents completely) followed by Pop Art (which deliberately used mass culture for its subjects) buried it for good.

The genres, however, have outlived the hierarchy. Freed from ranking, they remain tools for any artist to use, from fine art megastar David Hockney‘s 21st-century landscapes and portraits drawn on an iPad to illustrators depicting battles on worlds that could never be. And just as an eighteenth-century Academician who could not fathom digital art, much less Phyrexians, could have looked at Storm the Seedcore and recognized history painting, we in the twenty-first can look at the same piece and understand why history painting once ruled the Western art world.