Cave paintings in Indonesia, discovered in 2014 and among the oldest known paintings, depict simple geographical shapes and handprints. In 2017, archeologists found within these Sulawesi caves the oldest known cave painting: a drawing of a “pig-deer,” or babirusa. Look at that little guy go.

The 45,500-year-old painting is part of a series of babirusa paintings; this one is fascinating not just for being the oldest, but for what it depicts. The babirusa is facing two others, caught at a moment in time before mating or fighting or simply communicating. The artist(s) who painted this work understood the behaviors of the animals they hunted, and they had enough empathy or susceptibility to the pathetic fallacy to find that behavior worth capturing in art.

Other, younger paintings also suggest—or suggest to me, a layperson who is more of a romantic than your professional archeologist—the deep relationship between the creation of art and the understanding of yourself and your place within your environment. There’s a 35,500-year-old painting of a female babirusa that sticks with me. The art is crude, but recognizably a simplified drawing of an animal; notably, there’s also a line underline the babirusa’s hooves: a clear representation of the ground on which the animal stands. Even at the very beginning of the history of art, nascent artists found a way to anchor their abstractions, to place them within the context of the world.

Barbara Ehrenreich, predictably, writes more eloquently about this than I can, but there’s something tender and haunting about the way lost hominids understand the world around them—the solidity of the ground and the ephemerality of the flesh. In the way they ground up pigment, spat crude paint onto cave walls—trying, the same way we are trying, thousands of years later, to capture the whole span of it within our brief hours.

The babirusa still exists, even 45,000 years later—diminished, and threatened by the growth of the same species that used to paint them. But the people who hunted them and who captured them in ocher and char are as unknowable to us as any alien species. In 45,000 years, the same will be true to whatever comes after us.

By comparison to the Sulawesi paintings, the most famous European paintings—in the Lascaux caves in Southwestern France—are cutting edge. The distance between the two—approximately 28,000 years—is the temporal distance between Byzantine art and Banksy times fifty. Even still, the Lascaux cave paintings are so old—they were painted around 17,000 years ago, predating the Holocene—that the animals depicted are aurochs, a now extinct species of shaggy bovines (and one that old school Magic players may recognize). But again, much like the Sulawesi paintings, they are recognizable: no one alive has ever seen an aurochs, but a blob body with four legs reads as “cow” to both an ancient Magdalenian and a modern kindergartener.

Some archeologists speculate that the overlain lines on the Lascaux paintings and similarly aged paintings—circa 23,000-15,000 years ago—were a very early attempt at animation. Flickering torch or firelight would hit the rock walls and highlight the outlines erratically; by superimposing multiple outlines, the firelight would make it appear as though the animals were moving. “Why” is an open question: everything from “it was a way to honor the gods” to “optical illusions look cool.”

I was prompted to revisit this last week for two simple reasons: my social media feeds were replete with DALL-E mini creations and I was sorting a massive stack of 1,000-count boxes. DALL-E, for those less online, is an AI tool created by Boris Dayma that generates images based on a prompt provided by a user. DALL-E draws from existent material the machine is trained on, so it works best when prompted by either a celebrity or an archetype. So it does well with, say, Joe Biden or Guy Fieri, but it also can very easily pull off “witch” or “goblin.”

The more arcane, the less representational—which can lead to its own beautiful majesty, as when comedian/Twitter imp Stefan Heck used it to make a series of absurdist images. I’m not above silliness like that myself, and was shocked that the program recognized one of our jargon terms.

I took a spin to try to replicate some classic Magic art and started with Mogg Fanatic, for which my original prompt for DALL-E was “Oil painting of goblin falling from an aircraft.” While some of the elements were there, I wasn’t happy with the details, so I modified my search to get closer to the actual art. The most fascinating part of DALL-E lies in how it handles nuance—in trying to recreate Mogg Fanatic, I tried both “falling” and “leaping” and both “aircraft” and “airship” and got biplanes for “aircraft” and a pretty faithful dirigible for “airship.” “Oil painting goblin leaping from an airship” gave us this, which is surprisingly close to Brom’s classic art.

Even from such a simplified search, that middle top is shockingly passable. There’s something dreamlike about how machine art renders organic material. There’s no distinguishing feature that makes the goblin defined as a goblin, but even just as a multicolored blur, the proportions and hue read distinctly as “goblin.”

Other experiments were less successful. Unsure even after twenty years what, precisely, Tarmogoyf is, I defaulted to the original ‘Goyf and put in “monster eating skeleton in snow.” The less said about that, the better: I got a skeleton with a warped face and a greenish tinge sitting in the snow like Jack Torrance at the end of The Shining. I next tried “scaly monster digging skeleton out of the snow” and got this abomination:

Concerned I was doing permanent damage to my psyche and to the image of the Lhurgoyf, I moved on.

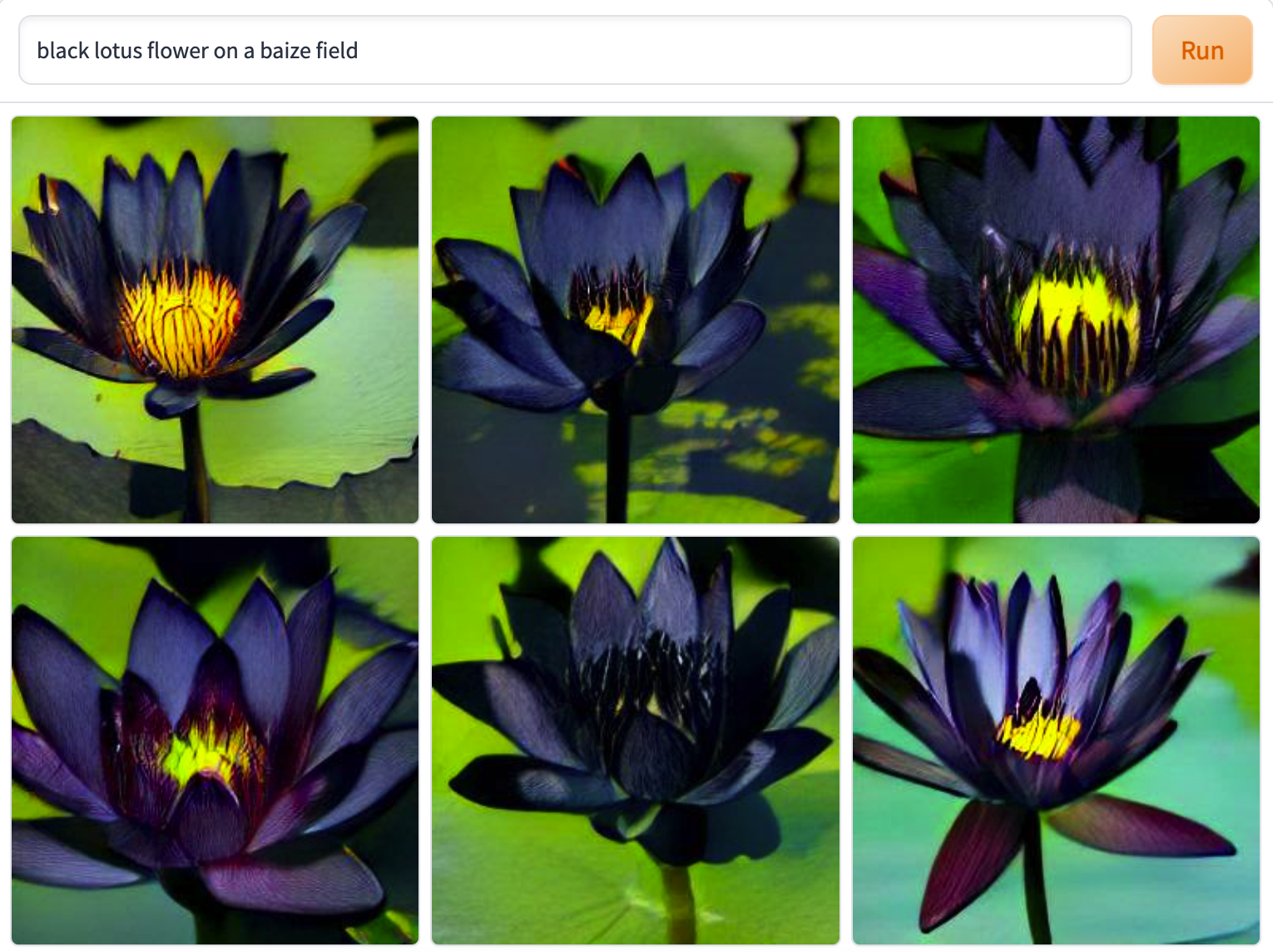

When we talk about iconic Magic art, it’s hard to beat Christopher Rush’s Black Lotus—not an especially accomplished piece, the myth of the game and basic human greed has made it an indelible part of the Magic aesthetic. “Black lotus flower on a baize field” gave us these results:

Pretty close, albeit anodyne—this is the first AI art that I’ve seen recently that concerns me. It’s not going to replace Magic art any time soon, as Magic’s plane-hopping nature and defined style guide are hard to replicate. But if we’re speaking in terms of artistic development, this is much more advanced that the Sulawesi cave paintings. Where the eye was drawn to the concreteness of the art, the solidity and presence of it, the eye drifts off of this.

We recently put in sound-baffling “art” panels at my office, and they have this same smeary, half-Impressionist texture, a kind of uncanny dentist-office-waiting-room vibe that makes me feel as though I can see the wallpaper in my future nursing home. This is the part of machine learning that gives me and artists pause—there’s a possible future in which the masses decide AI art and writing are good enough. I don’t think we’re there yet, even if we have accepted the commercial term “content” over the individualist term “art.”

If art is cooking, and commercial art is a McDonald’s combo meal, then DALL-E mini/Deep Dream/Midjourney/etc. is closer to making replica food out of Play-Doh. It’s not intended to sustain or nourish or fool anybody, and that’s why it’s taken off on Twitter, the platform for shitposting ephemeral eyesores and lobbing rhetorical bombs in the agora. Twitter is a nightmare of the algocracy, a bathroom wall in the Panopticon, a poorly-ventilated Tenement of Babel, where we type cacography like “Michael Bublé in seven-hour standoff with the FBI” and “Budd Dwyer uses the urinal next to Jar Jar Binks.”

Much like I’m not an archeologist, I’m not an artist. My niche is “dilettante,” meaning I know just enough about a lot of things to be fearful of the future and frustrated at my own ignorance. Some artists have come down hard against machine art as a degradation of their craft and the long hours spent honing their skills, managing their marketing presence, and summoning inspiration. I think that concern is valid, but, as it stands, DALL-E is a curiosity. There is art produced via machine learning that is much, much closer to a sort of mechanical Michelangelo, and it’s easy to imagine a world in which an art director is able to tweak an advanced form of AI artist to create what they need.

We’re lucky that Magic has such a commitment to traditional modes of art and, as recently as Double Masters 2, has reaffirmed that commitment. Ian Miller’s Damnation, Donato Giancola’s Golgari Rot Farm, Scott M. Fisher’s Bloom Tender—these are statements against the grey-goo-harbinger of “content” from artists who have been a part of the game for decades.

Magic’s greatest strength outside of its gameplay is its art. Not only is it generally an entire order of magnitude above art from other games, the hours spent playing these cards means most players have a connection to the art that goes beyond the aesthetic to the emotional. Sleeves, playmats, posters, alters—there wouldn’t exist this entire interlocked series of economies without Magic’s dedication to its art. We’ve come a long way since our distant relatives ground ocher into paint. Hell, we’ve come a long way since our relatives whisked pigment into egg yolks, but we’re simply at a later point in that same legacy. Paintings of pig-deer have given way to paintings of Tarmogoyfs, but no machine can guide the eye and the hand the way a lifetime spent training and a burning drive to capture the world or suggest the possible will.

A lifelong resident of the Carolinas and a graduate of the University of North Carolina, Rob has played Magic since he picked a Darkling Stalker up off the soccer field at summer camp. He works for nonprofits as an educational strategies developer and, in his off-hours, enjoys writing fiction, playing games, and exploring new beers.