How much story can you tell in four cards? How large a world can you birth? How much can it matter?

These are questions that, amidst the ongoing deluge of Magic product, have been on my mind, The reason I spend so much time thinking about Magic isn’t just that I love doing silly stuff in EDH (though I do), it’s that I can find a spark of life in Magic’s worlds—the sense of an expansive, living, entirely and beautifully unnecessary alternate reality sandwiched between the front and back sides of cardboard.

And the more stuff there is, the harder it becomes to feel the spark’s glow. This is particularly true given the deluge of Universes Beyond sets, which either don’t tell stories at all (like Marvel’s Spider-Man and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) or that can only reproduce existing ones (like Avatar: The Last Airbender).

So, I ask again, when original stories and living worlds seem to occupy proportionately fewer cards, how much story can fit in just a few cards?

Kieran Yanner’s Lord of the Pit, from his recent Artist Series Secret Lair

I wager that the Secret Lair Artist Series offers an answer.

It’s a little ironic, I know, to approach Artist Series Secret Lairs as little gems of truly magical Magic. After all, the Secret Lair sub-brand is the particular corner of Magic where high prices, cutthroat aftermarket speculation, and sometimes-exploitative commercialism come together most clearly.

But Artist Series resist pure consumer logic; they radiate beauty in excess of their functionality, and what’s more, they tell stories. And I wager that, as limit cases, they can show us the weird, small, beautiful ways Magic’s artists can bring fantasy worlds to life.

A Story in Four Acts

Notionally, Artist Series Secret Lairs are purely visual showcases. They’re an opportunity for Magic’s greatest artists to flex their talents in a self-contained series of cards.

But in practice, Artist Series are also deeply literary. New art and original flavor text work together to birth narratives–to make a story out of a gallery show.

This is the case for the Artist Series Secret Lairs of Ryan Alexander Lee, Sidharth Chaturvedi, and Johannes Voss.

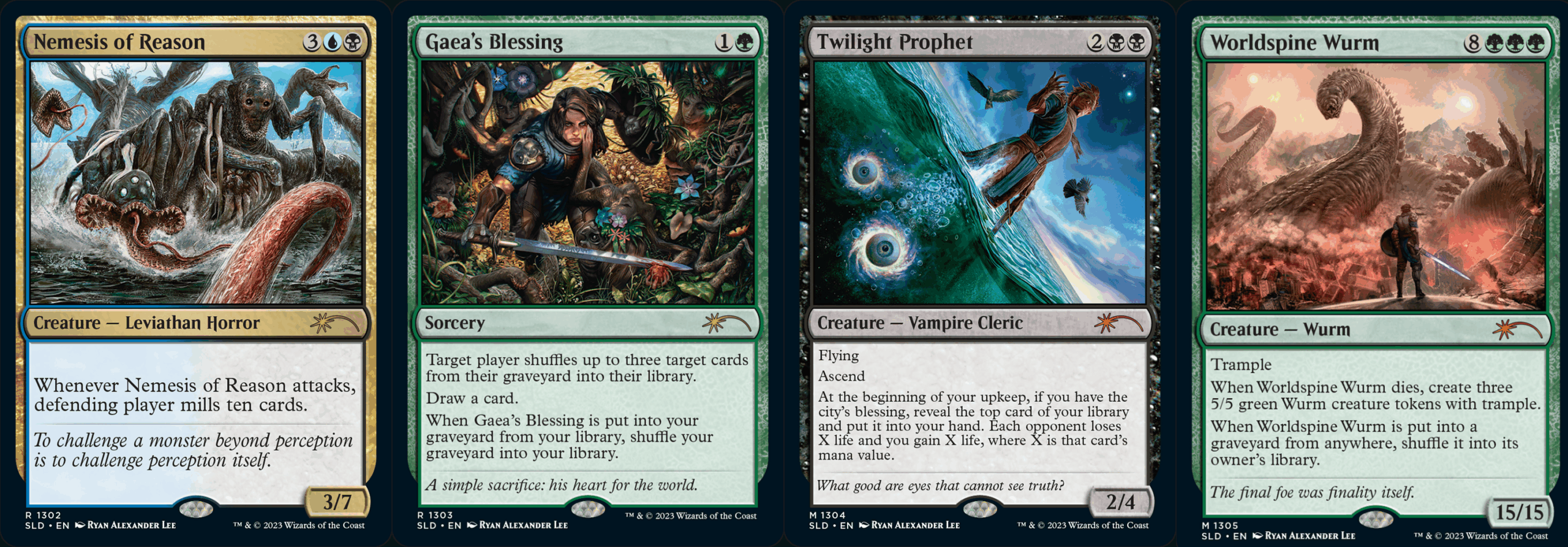

A polyptych of Ryan Alexander Lee’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Nemesis of Reason, Gaea’s Blessing, Twilight Prophet, and Worldspine Wurm

Lee’s, inspired by heavy metal album liners, tells an epic fantasy tale about a hero who’s challenged by unimaginable monsters (namely Nemesis of Reason, makes tremendous sacrifices in Gaea’s Blessing, Twilight Prophet ), and finally faces off against the embodiment of mortality (in Worldspine Wurm ).

It wasn’t until writing this article that I savored the trajectory of Lee’s story. Its epic quest isn’t about generic evil, it’s about the limits of human understanding itself: the protagonist is forced to strip away everything anchoring him to human perception–even his eyes, in Twilight Prophet—in order to face the darkness at the very fringes of existence.

Chaturvedi on the other hand, tells a story rooted in kinship and legacy.

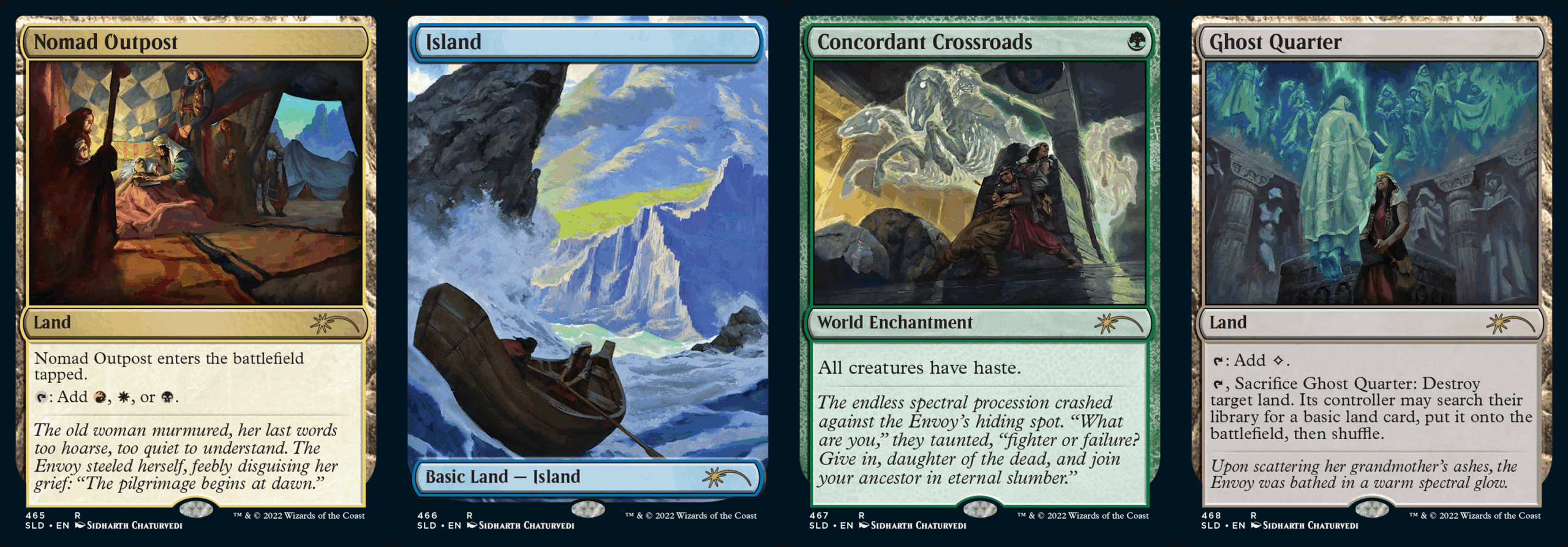

A polyptych of Sidharth Chaturvedi’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Nomad Outpost, Island, Concordant Crossroads, and Ghost Quarter

A grieving young woman—known only as ‘the Envoy”—makes a pilgrimage from her home to scatter her grandmother’s ashes, moving through rushing river rapids, facing taunting ghostly monsters, and finally finding peace at the end of her journey.

The flavor text here is intensely moving, but what I’m most impressed by is Chaturvedi’s ability to land a story beat through a land, of all things, in his Island.

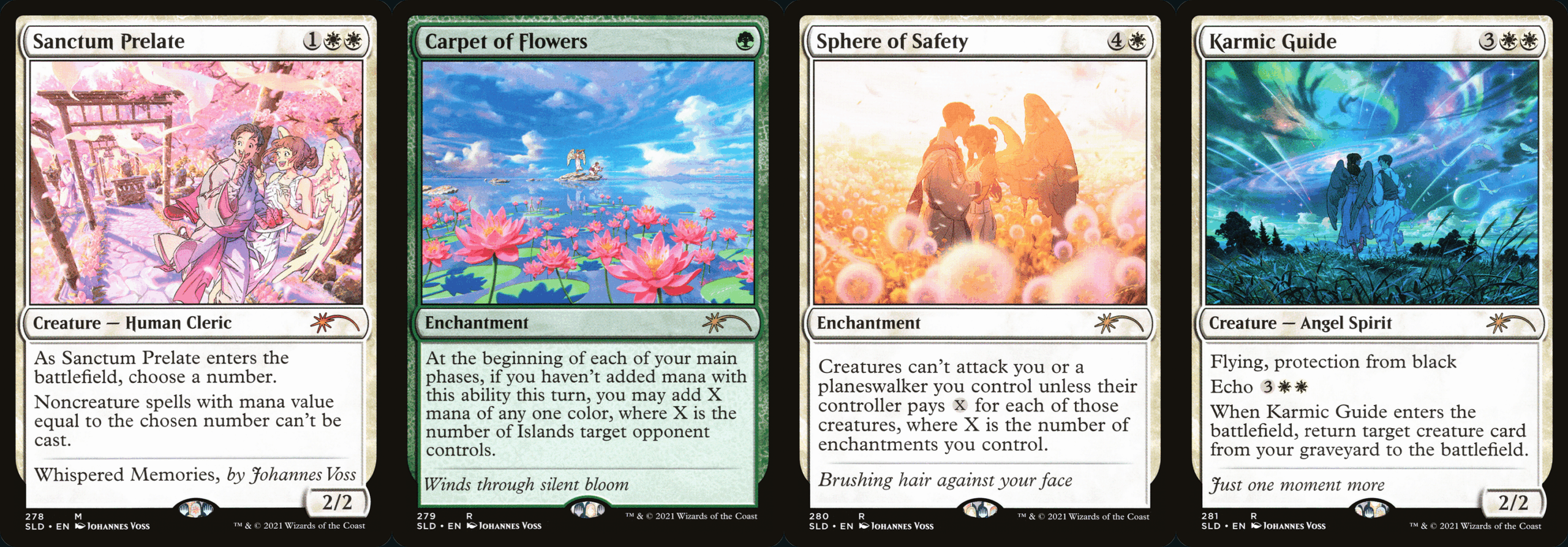

A polyptych of Johannes Voss’ Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Sanctum Prelate, Carpet of Flowers, Sphere of Safety, and Karmic Guide

Voss’ Secret Lair, for its part, is deeply poetic. While the art depicts different scenes from a romance between an angel and a human, the flavor text comprises a haiku, entitled “Whispered Memories,” written by Voss himself:

Winds through silent bloom

Brushing hair against your face

Just one moment more.

The beaming bright colors of Voss’ illustration visually links the couple’s quiet harmony with of the abounding natural world. The flavor text, in its turn, infuses the story with tender solemnity. As the protagonists walk toward the nebula-sprayed horizon, they are also walking into infinity.

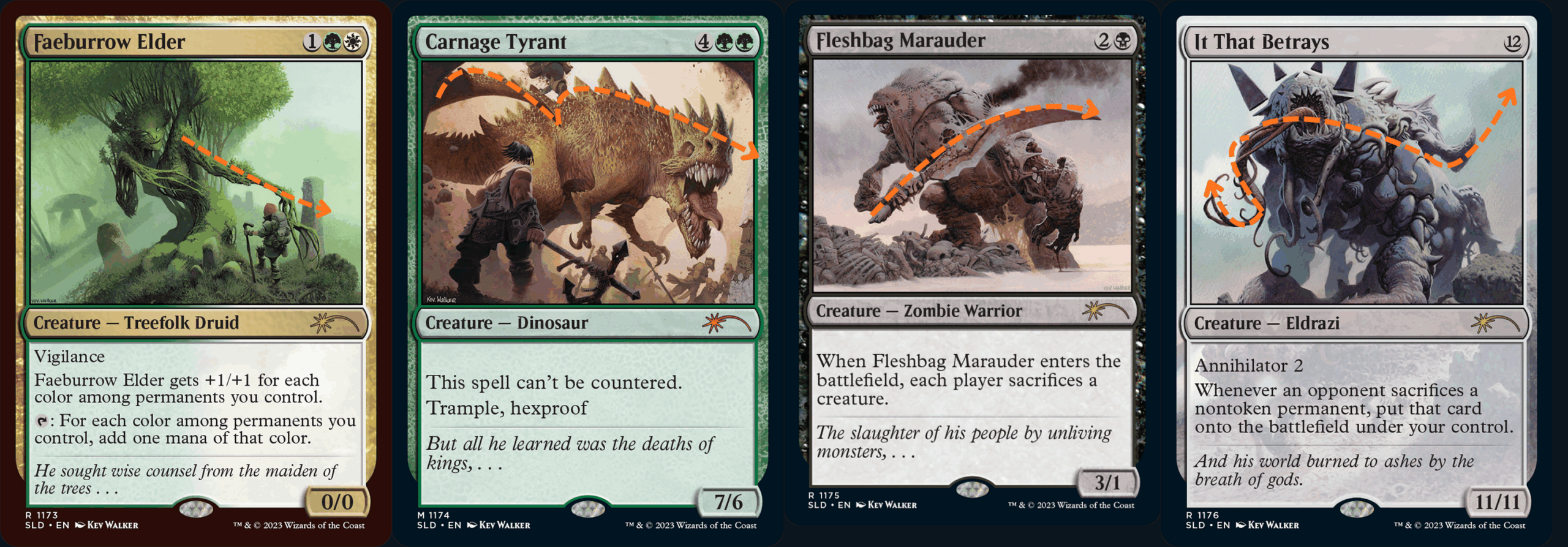

A polyptych of Kev Walker’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Faeburrow Elder, Carnage Tyrant, Fleshbag Marauder, and It That Betrays

But my most favorite Artist Series narrative is Kev Walker’s. In SLD #1173 through #1176, Walker—a veritable titan of Magic art—illustrates and composes a narrative of degradation, despair, and collapse.

This is a story riven with conflict and freighted with psychic pain. Characteristically, Walker’s compositions comprise large shapes made of soft lines and muted colors.

This is the story of a world dominated by titanic, unknowable entities. All of Walker’s chosen cards are all large, hulking creatures (the exception is Fleshbag Marauder, which Walker sizes up from previous iterations).

This is a story of humans made small, visually and existentially. Human figures are scant and take up only fractions of the canvas–occupying only a tiny part of the bottom right corner of [Faeburrow Elder, the tapering bottom third of Carnage Tyrant, and zero percent of It That Betrays.

Taken in isolation, these images might read as vignettes from a dark world. But Walker’s flavor text grasps them together to make somethingmore unsettling.

He sought wise counsel from the maiden of the trees…

But all he learned was the deaths of kings,…

The slaughter of his people by unliving monsters,…

And his world burned to ashes by the breath of gods.

While the Secret Lair’s official description bills the narrative as “a hero’s hopeless crusade against the cruelty of the gods,” I read this mini-narrative poem as something else. A crusade implies battle, will, the possibility of action. Instead, I read this as a story of agonizing, mind-splintering revelation– one that educes the horror of Magic’s great, titanic monsters.

Kev Walker’s version of Faeburrow Elder

Framed this way, we can see a story becoming legible across the four cards in Walker’s series. Our unnamed protagonist begins his journey by meeting with the most benign titanic creature: an emerald-mantled treefolk, whose size triples the journeyer’s and whose undulating form evokes the wise and unsettling serpents of wisdom literature. Her lips, such as they are, curve into a smile that’s at once welcoming and menacing, and her tendriling fingers seem to enwrap our journeyer.

Kev Walker’s It That Betrays

The next illustrations read like the apocalyptic visions of Revelation. As the central creatures move further away from the realm of the human (dinosaur, undead, otherworldly) the flavor text scales up into new tiers of destruction: the fall of heroes, the extermination of species, the annihilation of the world.

A polyptych of Kev Walker’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Faeburrow Elder, Carnage Tyrant, Fleshbag Marauder, and It That Betrays, with a line added by me to trace the movement of the eye across the four paintings.

And in the end, there is no succor, only a return to the cycle. Reading the images side-by-by-side, we might notice how the first three images guide the reader’s eyes to the right, as though forcing us to glide along to the next vignette of annihilation: the Faeburrow Elder’s fingers draw the eye into the Carnage Tyrant’s sweeping tail, which itself points to the crescent hook of the Fleshbag Marauder’s blade, which itself points us to the It That Betrays curling tongue, whcih in turn moves us through its angled body and to the empty horizon at the far right. The end of the line.

We might trace the trail back, moving back along the horizontal lines to the Faeburrow Elder. But if we do, we have nowhere to go except back the way we came, back into the nightmare. Unknowable destruction and the futility of the human being: this is the origin and endpoint of Walker’s story.

The narrative told here is one far more condensed, and perhaps far more experimental, than those typically told in Magic fiction. With certain recent exceptions, we don’t often go to Magic story for its mindbending dread (cynically, I wonder if this is because stories of cinematic adventure make for more return customers than existential angst, but that’s maybe a little unfair)—and Walker’s Artist Series gives us the chance to inhabit this sort of narrative.

More than that, though, Walker and Chaturvedi and Lee and Voss all demonstrate how much four cards can do in telling a story. Imagined side-by-side rather than as fragmentary individuals, specific cards can forge narratives told in the act of looking.

I wonder what it might look like for more Magic story to acreage this sort of narrative. Certainly, there are cards that set up story beats or that tell stories through their mechanics, but it’s rare to be taken through a serial story across multiple cards. To be sure, it’s risky: you can’t tell a three-act story in non-Secret Lair Magic cards, because they might be seen or played out of order or with a chapter missing.

But perhaps that limitation can stimulate creativity. It might allow for stories that are episodic, ephemeral, and willing to play around with linearity, as Walker’s does.

A Feel for the World

Other Secret Lair Artist Series do something entirely different. They do not weave narratives, but instead give us ways of experiencing the amorphous feeling of a living fantasy world.

What I mean is that they don’t create their worlds by way of abstract information—they make us experience existential otherness.

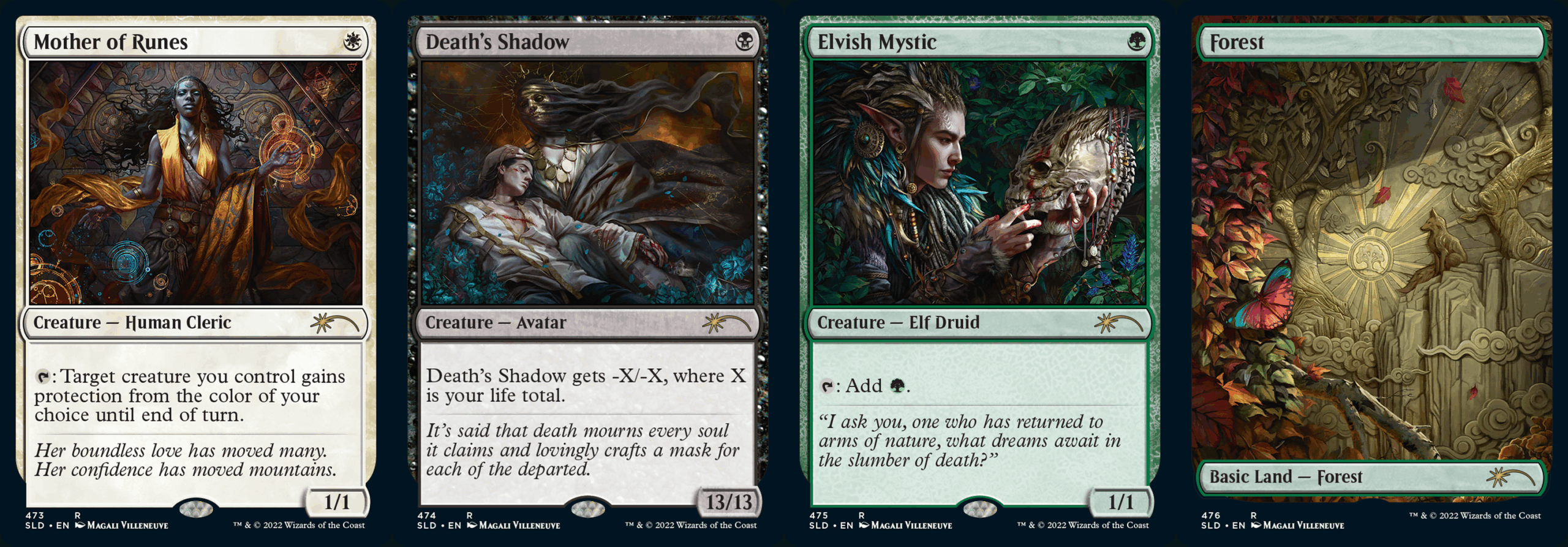

A polyptych of Magali Villeneuve’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Mother of Runes, Death’s Shadow, Elvish Mystic, and a basic Forest

Magali Villeneuve’s Artist Series is one such example. The series’ imagery, characteristic of Villeneuve’s rightfully acclaimed style, blends high fantasy content with the decadence of the Pre-Raphaelites and the esoteric drama of Symbolist art—resulting in a Secret Lair whose world drips with mystery. The images we hold in cardboard or that we view on our screens are tiny dark hagiographic icons, glimpses into the ineffable.

The full art of Magali Villeneuve’s Pieta-like “Death’s Shadow”

The effect is amplified by the flavor text that Villeneuve collaborated with Wizards of the Coast to create. The flavor for Death’s Shadow, my favorite of the set, takes a sharp departure from the menacing original and instead, like the Pietà the images references, evokes divine mercy:

“It’s said that death mourns every soul it claims and lovingly crafts a mask for each of the departed.”

As Rob Bockman has wisely said, the art “changes how it feels to employ the card. We’re not a berserker, sacrificing our life so we can power up our symbiotic Avatar, but a broken failure, relying on a protector to get our revenge from the threshold of death.”

The full art of Magali Villeneuve’s “Elvish Mystic,” who ponders a skull like Hamlet contemplating the remains of Yorick

In these four cards, Villeneuve summons a world that is built from fantasy imagery but points to something ineffable. This is a world of elves and spirits and clerics, to be sure, but they come from dark primordial sacristies and catacombs rather than the pages of the Dungeon Master’s Guide. They do not spend all their time slinging arrows and casting spells, but rather, like the Hamletesque subject of Elvish Mystic, grapple with questions of existential import.

Villeneuve’s imagery refuses to let us stop at the surface; this is not a world guide. She make us go beyond, into the arcane and mystical style of existence latent in them.

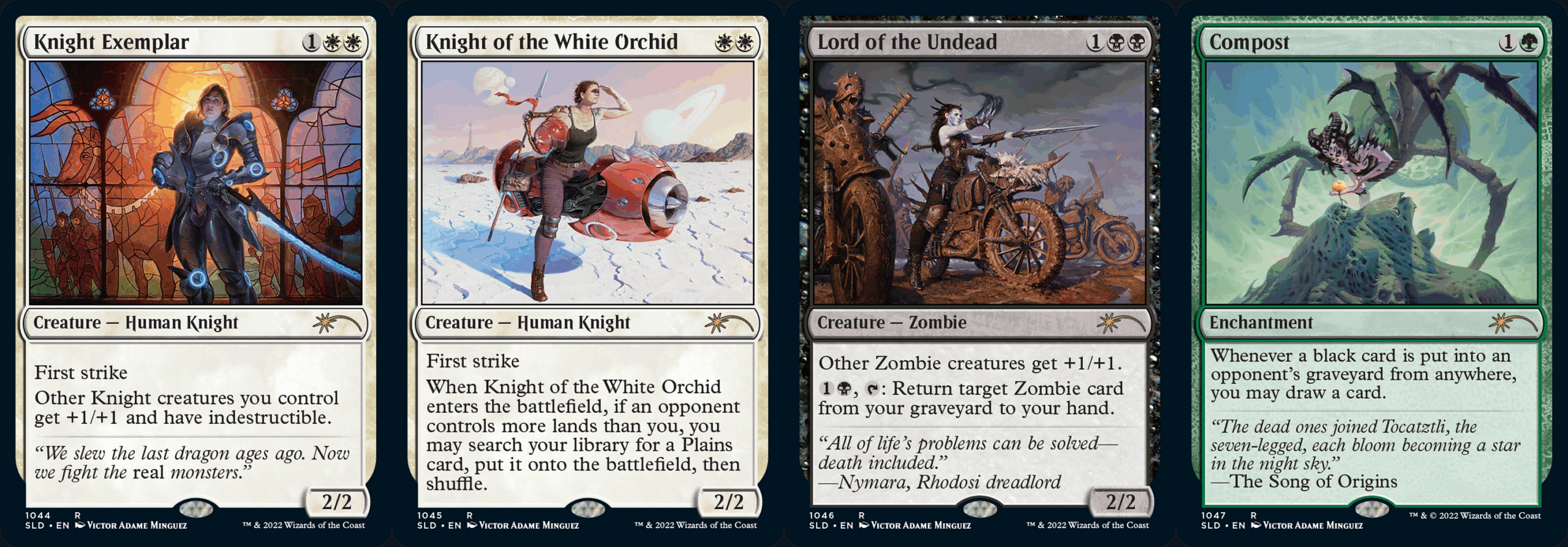

A polyptych of Victor Adame Minguez’s Secret Lair Artist Series, featuring Knight Exemplar, Knight of the White Orchid, Lord of the Undead, and Compost

In a similar way, Victor Adame Minguez’s Secret Lair is (to my mind), one of the best of all time. That’s not just because his art is technically enchanting (though it is), but rather because he uses existing fantasy vocabularies to evoke a living, dynamic universe.

On one hand, it’s possible to break down each image into a high-concept description: Knight Exemplar is a chivalric hero of the future; Knight of the White Orchid is an interstellar adventurer on a seemingly barren world; Lord of the Undead is the imperious leader of a postapocalyptic zombie motorcycle gang; and Compost is an arachnid god cradling a flower in golden bloom.

But Minguez’s skill as a painterly storyteller—and his work with the flavor text team—ensures that these images point to a world beyond such broad archetypes.

Full art of Victor Adame Minguez’s Knight Exemplar.

Knight Exemplar tells its story with both composition and light. The titular knight poses in front of, and also is absorbed within, a stained glass image (whose imagery homages Jason Chan’s original Knight Exemplar). She’d at once embedded in and breaking out from the canonical imagery of action fantasy. The exuberant warm glow that illuminates the glass flares like a halo around her head, but it also contrasts with the icy blue glow of her futuristic armor. Zoom in enough and you’ll see that the knight’s face is flecked with blood and grime. It’s an almost entirely unnecessary detail in a painting already so attractive, but this sort of granular detail makes Minguez’s world feel alive.

The same vivifying detail dots the other paintings. What is the Akira-esque Knight of the White Orchid—her helmet etched with the titular flower—looking for on this faraway world, and does it have to do with her cybernetic arm? Why does the Lord of the Undead wear facepaint like a Scottish tribal warrior as they command their desiccated minions? What gentleness animates the spider-god’s tiny little smile behind her skeleton facepaint, and in view of the calcified bodies from which the flower sprouts, is it somehow melancholy?

To be clear, these are all rhetorical questions. They’re not to be posed seriously (save perhaps by people whose eyes twitch if they encounter something without its own Wookiepedia article). But they speak to the underlying pulse of mystery latent in these paintings, their ability to summon a fantasy world that feels alive and full of meaning but that isn’t entirely answerable.

We shouldn’t discount this feeling, the sense of a world that invites but withholds. Uninteresting fantasy storytelling (including some Magic sets from the last few years) does not know how to embrace unknowability. It’s fantasy as a middling Netflix original film, making recourse to pre-given pop-culture vocabularies and aspiring to nothing more than the merely interesting.

Victor Adame Minguez’s “Compost”

Instead, Minguez’s and Villeneuve’s Secret Lairs draw on existing vocabularies but open the door to a world beyond tropes. Minguez gives us enough high-concept imagery to entice us, to help us feel the incandescent warmth of each painting’s world—the futuristic kingdom, the bone-bleached exoplanetary desert, the post-apocalyptic heavy-metal fever dream, the mystical nexus of all life—but also populates them with meanings that escape our grasp.

In this, I want to say, Minguez’s and Villeneuve’s Secret Lairs condense the best of Magic worldbuilding. They don’t breathlessly try to explain a world to us or half-baked send-ups to pop culture, but rather operate on the level of feeling.

What kind of worldbuilding is this? At its best, this is worldbuilding that allows for trope and archetype without becoming lost in them. It recognizes that we have a cultural vocabulary, but puts the words in new combinations and with new accents to draw out mystery and intrigue. This is fantasy storytelling in which a world’s endpoint isn’t a specific cultural or pop-cultural aesthetic (Norse, Egyptian, racecars, detectives), but rather an encounter with the unknown through those aesthetics.

For a Limited Time

One part of me wants to hold up the Artist Series Secret Lairs as the benchmark for Magic storytelling and worldbuilding—and as you’ve seen, I have plenty to say even about these five. And that’s to say nothing of my favorites not listed here (Jesper Ejsing, Alayna Danner, Livia Prima, and Rovina Cai’s Secret Lairs are all stellar).

Yet the knotty difficulty with Artist Series is that their storytelling power is highly situational, seemingly set apart from the standard method of Magic storytelling and worldbuilding.

Because Secret Lair are, at least notionally, bought all at once rather than harvested from booster boxes, it’s easy to ensure they crystallize a unified aesthetic experience. A buyer gets all four Kev Walker cards, so they get the whole story. It’s difficult to export the storytelling model of a Secret Lair to a full Magic set, I mean, because the experience of a Magic set is necessarily more fragmented.

Still, precisely because they’re exceptions to the rule, Artist Series Secret Lairs give us the chance to reflect on the core of storytelling-by-cardboard.

My hope is that the artists and storytellers of Magic, official and otherwise, can recognize the power emergent in these series. They help us see what might be possible, and what’s already being done to create life in four cards.

Ryan Carroll (he/him) is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English and Comparative Literature. On Substack as Dominarian Plowshare, he writes about Magic’s art, story, and experience. Outside of Magic, he writes on topics including 19th-century literature, information theory, television politics, and cliche.