I’ve always had a problem with the unknown.

By the unknown, I mean that place that’s really, truly, totally inaccessible. Gone; null; nothing. As a child, I was scared of the dark and of its distant cousin, oblivion.

When things disappear, I wondered, where do they go?

Gravkill by Dominik Mayer

As an adult, I love brushing up against the unknown. I read and study the British and American literature of the nineteenth century, whose encrusted Protestant orthodoxy broke open with anxieties about the relationship between the material and the spiritual. This was a moment when Edgar Allan Poe wrote stories about guys who receive extremely specific visions from the beyond and then melt into goo; when spirit mediums dictated books by the ghosts of Thomas Paine and Ben Franklin; and when Elizabeth Stuart Phelp’s hugely popular novel The Gates Ajar describes Heaven as, basically, a 1950s gated community.

Fire Lord Zuko by Jo Cordisco

All of this was in my mind when I was recently looking at the Avatar: The Last Airbender card Fire Lord Zuko, whose second line reads: “Whenever you cast a spell from exile and whenever a permanent you control enters from exile, put a +1/+1 counter on each creature you control..”

Exile, as its name vaguely implies, is the closest thing in Magic to the unknown, the beyond, the totally absent: it is nothing. And yet, cards like Zuko presume that exile is, too, a resource we might exploit.

So what is exile? And how is it we presume to bring things back from it?

Into the Unknown

As of the time of writing— sure to change, since Lorwyn Eclipsed previews are dropping as we speak (hey, doesn’t the new Doran look cool?)—there are 2542 cards that mention exile. Both the mechanic and the zone of total unknownness it represents have changed quite a lot over the course of that long history.

Animate Dead by Anson Maddocks

It bears asking, first, why we have exile at all. Typically, we might think of death as being the unreachable unknown, the horizon of human existence itself—and in the early days of Magic, as now, death is represented by the graveyard. Except, importantly, Magic’s high-fantasy, folkloric, and religious source material already prepared it to transgress death: in Alpha, Resurrection and Animate Dead could bring creaturs back from the grave,

And yet game mechanics and flavor still necessitated a horizon: there must be something beyond death, something so removed that even a reanimation spell would be futile. Enter: exile.

Disintigrate by Anson Maddocks

The very first cards that referred to exile appeared in Alpha: one, the nigh-on unknown Disintegrate, last reprinted in Fourth Edition, and the other, the now-immortal Swords to Plowshares, last reprinted in every Commander product ever. Their pithy revised Oracle text reads:

Disintegrate: “Disintegrate deals X damage to any target. If it’s a creature, it can’t be regenerated this turn, and if it would die this turn, exile it instead.”

Swords to Plowshares; “Exile target creature. Its controller gains life equal to its power.”

But the Alpha rules text, composed before game mechanics were tightened and standardized, before the word “Exile” had even been codified as a noun or verb, was different. It was more emphatic, and thus somehow more portentous:

Swords to Plowshares by Jeff Menges

“Target creature is removed from the game entirely; return to owner’s deck only when game is over.” The adverbs entirely and only are insistent in a way that’s unusual for the cold language of game rules—we certainly don’t see it in modern Magic cards. This older text goes over the top, as though it needs to convince an incredulous player: No, really, those cards are gone.

And of course, it makes sense that players would need convincing.The mechanic is existentially unsettling in its simplicity. Short of physically destroying the cards, there is nothing more potent. Until the end of the game, they simply don’t exist; they are, at least for the next few minutes, annihilated.

Urza’s Ruinous Blast by Noah Bradley

As Wizards of the Coast designer and writer Doug Beyer put it in 2008, exile is a region beyond death, a realm of extreme gone-ness known as the removed-from-the-game zone”:

In flavor terms, the removed-from-the-game zone is oblivion. It’s a realm beyond the penetrating eye of the mind, not subject to coherent thought. Whether it’s a conceptual state of being, some far-off but physically real place, or some metaphysical condition of existence failure, is something only thaumaturgically reckless mages dare contemplate. It is as far from existing as a thing can be, and yet the zone has echoes of causality that do occasionally impinge on the multiverse and those within it. When your Dragon Fodder ends up in the not-here of this zone, best forget about it. There’s no path between you and your spell. Leaving aside some seriously freakish spellcraft, it’s gone.

There’s real dizzying power in this concept. It’s entirely normal, of course, for games to designate illegal or inaccessible zones—a baseball fielder can’t run into the stands; my couch is not a part of my Monopoly set—but in Magic, the exile zone sizzles with metaphysical danger, threatening illogic. What do you mean my card doesn’t exist? I’m looking right at it, aren’t I? Exile subjects us to the awful and unimaginable answer: No. It doesn’t exist. You’ll only get it back when the game is over. To play with this mechanic is to encounter the infinite, in all its horror and incomprehensibility.

But even so, Magic’s development has proposed that even exile isn’t final.

No Stone Unturned

Over the course of Magic’s history, the game has found a way into the unknowable zone signified by exile—and sought to make it known. In fact, such experimentation is only a little younger than Exile itself.

Return to Dust by Wayne Reynolds

Indeed, Magic’s early sets played around quite a lot with different kinds of gone. In the first ever expansion, Arabian Nights, Ring of Ma’rûf allowed players to yank in cards from outside of the game, anticipating “wish” mechanics—dealing not exactly with oblivion, but certainly with some numinous metaphysical elsewhere.

Antiquities’ Tawnos’s Coffin toys with something a lot like phasing: a creature is made to disappear, but they keep all their auras and counters remain on them while they’re gone, and they come back when the Coffin is destroyed.

And Bronze Tablet draws on an old and strange game mode called ante, which was meant to add extra stakes to a game of Magic: cards you lost actually became your opponent’s, permanently. This isn’t the horrifying oblivion of death, it’s the horrifying oblivion of…private property ownership.

But these were all just preludes. In August 1994, oblivion was breached.

Safe Haven by Christopher Rush

The Dark’s Safe Haven gave players, for the first time, the ability to return creatures after they had been removed from the game. Your Hurloon Minotaur could see the other side of eternity and then return to tell the tale.

Something important happened here, mechanically: being “removed from the game” could now be another resource or strategy that players could manage–at once outside of the game and in it.

Flicker by Douglas Shuler

The possibility that the removed-from-the-game-zone (officially branded exile in 2010) could be controlled, could be used as a resource, would inform a whole host of mechanics that are now common. Safe Haven paved the way for the mechanical category that borrowed its name, which used exile to protect creatures, rather than consign them to utter nothingness. But 1999, five years after Safe Haven changed the rules of the universe, the mechanic flicker appeared for the first time (on, who’d have thunk it, Flicker), giving players the power to dip a target into the unknown and then yank them back out. This audacious power would spawn archetypes and subarchetypes unto itself.

Etali, Primal Storm by Raymond Swanland

Many other cards propose to plumb oblivion, whether as a temporary visit or as permanent conquest. Think of Etali, Primal Storm and Mimeoplasm, Revered One exile cards with a special brand, allowing players to use them immediately or later.

Chandra, Pyromaster by Winona Nelson

Chandra, Pyromaster and all its impulse draw descendents let players fling a card into nothingness and then claw it back for just a moment.

Seize the Storm by Deruchenko Alexander

The occasional card can peer into the void and count its contents, like Seize the Storm and Cosmogoyf.

Ashiok, Nightmare Muse by Raymond Swanland

Perhaps the most audacious of all, Ashiok, Nightmare Muse can actually tear opponents’ cards directly out of the void and hurl them back into their face.

As the exile zone transformed from unthinkable void to a largely-unaccessible-but-still-sometimes-accessible resource, older mechanical experiments were brought into the fold, standardized in the Oracle. Where Knowledge Vault and Necropotence initially referred to “tak[ing] a card without looking” or “Set[tting] aside” a card, they now simply read “exile face-down.” We see this revision’s legacy in mechanics like Imprint, Void, Plot, Madness, and Suspend. In such cases, exile isn’t permanent oblivion, it’s just a cosmic double-park zone for cards that are waiting to be used–or perhaps (as a friend suggested to me) sleep, inaccessible but somehow more domesticated.

In short, the exile zone has changed. In many ways, it still thrums with eerie finality, the possibility of going and never returning—but it’s also been converted into a game resource. Its haunting absence has become a half-realized presence.

Return to the Battlefield

The exile zone’s transformation represents something remarkably interesting about the way a game can grow, the way that a living game can push at the limits of its own existence.

Backslide by Pete Venters

When you have a closed system like a rules-bound game, it seems fairly easy to differentiate between a meaningful game event and a non-meaningful one. In baseball (some might be inclined to think), it’s a meaningful event when a player hits a home-run; it’s a non-meaningful event when I eat my popcorn in the stadium. In Alpha, when a card is exiled with Swords to Plowshares, it turns from a meaningful object into a non-meaningful object, no more relevant to the game than the piece of gum in my pocket.

But when a game grows and expands—when it becomes subject to transformation and innovation, new products and mechanics and power levels—the boundary between meaningful and non-meaningful object ripples. An exiled card is non-meaningful—except Ashiok, Nightmare Muse or Cosmogoyf suddenly makes it meaningful objects.

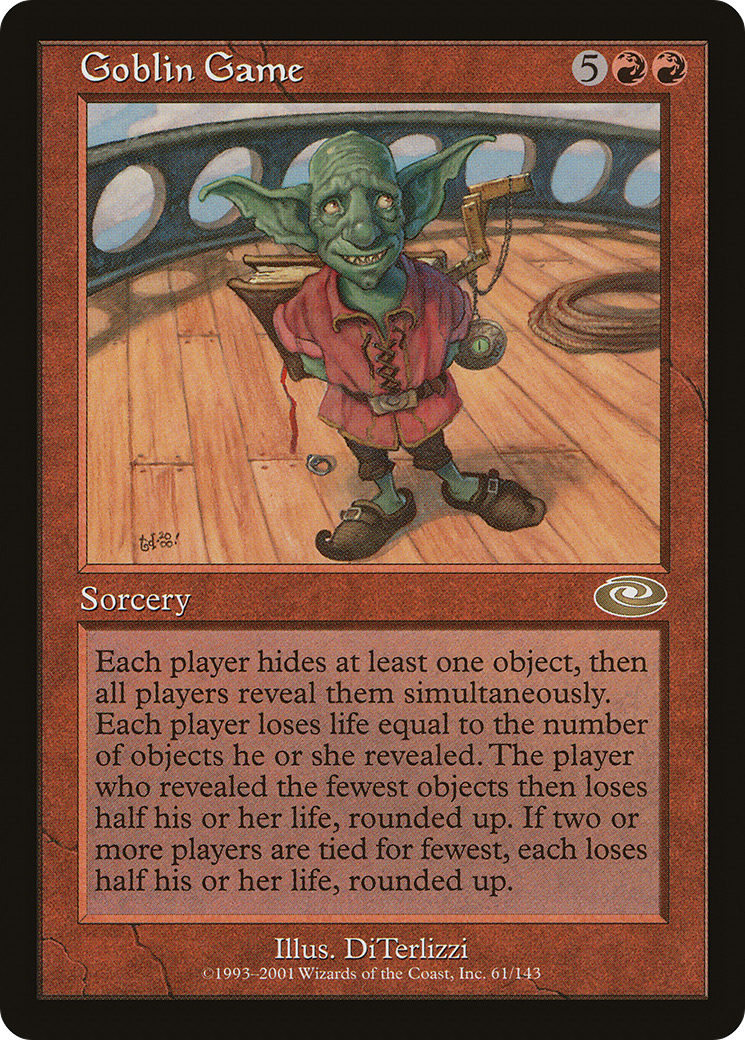

Goblin Game by Tony DiTerlizzi

This instability spreads; each example we conjure finds an exception. A card outside of my deck is non-meaningful, unless I’m running Death Wish. My physical surroundings are non-meaningful, unless I play Goblin Game. An audience member is a non-meaningful part of a baseball game, unless they reach out their glove, catch a ball soaring at the fringe of the field, and turn a hit into a homerun.

Path of the Ghost Hunter by Eli Minaya

All these are fringe cases, but they point to the strange whirring machinery inside a game like Magic. The exile zone’s power is that it draws us to notice Magic’s own perpetual transformation—to see the unsteady line between what’s gone and what’s here, what’s part of the game and what, supposedly, isn’t.

And so, to return to the question my younger self posed: Where do things go when they disappear? My answer: perhaps far away, but perhaps nearer than we think.

Ryan Carroll (he/him) is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English and Comparative Literature. Writing on Substack as Dominarian Plowshare, he thinks about Magic’s art, story, and experience. Outside of Magic, he writes on topics including 19th-century literature, information theory, television politics, and cliche.