Before I knew what Lorwyn was, it defined my understanding of Magic.

This is a little funny, because the Lorwyn–Shadowmoor megablock long preceded my entry into the game (and, for that matter, my entry into middle school). But when I was first getting into Magic by way of a cheap Selesnya tokens deck a friend built and bought and played with me over Zoom—before I knew what a set was or the difference between Lorwyn, Ravnica, Amonkhet, and so on—Lorwyn illustrations gave me my first, confounding impression of the world of Magic: The Gathering.

It was not an instant love affair. At the time, my taste in fantasy art was trained by the popping colors and cinematic illustrations of modern comic book art (my favorites were Dustin Weaver and Jim Cheung), so I was perplexed and a little put off by the sepia colors and the mixed irrealism-realism of Lorwyn’s art.

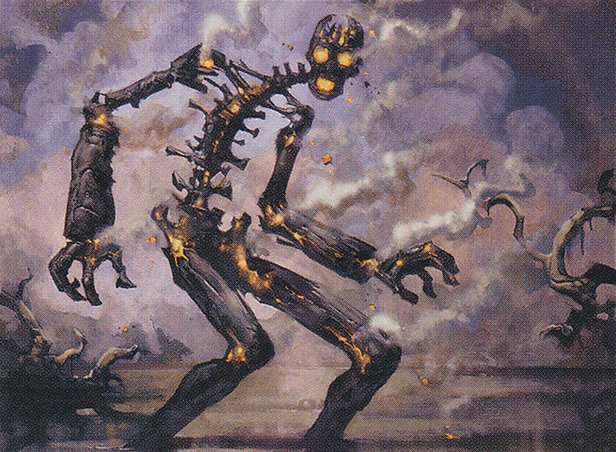

Cinderbones by Carl Critchlow

Dave Kendall’s Antler Skullkin and Dave Allsop’s Duergar Cave-Guard were grotesque and unsettling. Steve Prescott’s Brigid, Hero of Kinsbaile and Rhys the Exiled the former with her weird oversized head and the latter with his strange, slim, angular body, defied the visual vocabulary through which I conceived halflings and elves. Carl Critchlow’s masterpiece Cinderbones pulsed with a dark horror that was foreign to my understanding of fantasy.

This imagery defined my early engagement with Magic. I took its worlds to be strange, odd, and a little ugly, off-beat from the conventional fantasy realism that I knew.

For that reason, it’s been fascinating to encounter the Lorwyn-Shadowmoor, now first-order rather than as the distant past, in Lorwyn Eclipsed. I’ve loved the set and have been gobsmacked by its illustrations, its vibrant colors and striking imagery and arresting worldbuilding. But the specter of weird, unsettling Lorwyn lurked in the back of my mind. Something had changed, even if I didn’t know what.

In fact, as I’ve found, the character of our “new” Lorwyn-Shadowmoor can be traced in just a few paintings, by two artists of Lorwyn’s elves. In those three paintings is the history of this world—what disappears and what remains.

Outside Looking In

To be sure, it’s not surprising that Lorwyn and its visual language has changed.

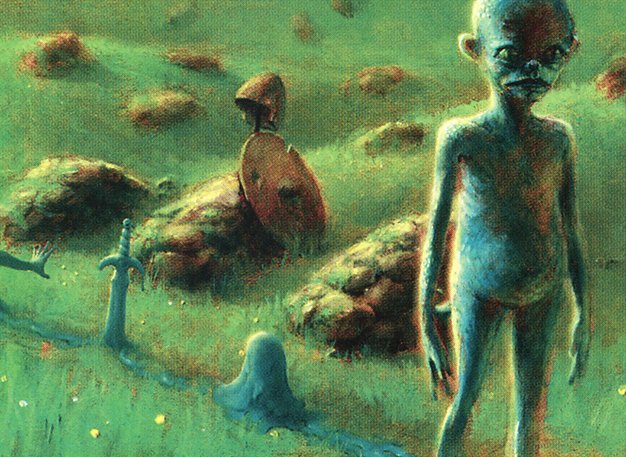

Cairn Wanderer by Nils Hamm

The time Magic has spent away from Lorwyn is the longest gap between sets based on the same plane. Here are the four largest gaps:

- 18 years have elapsed between the end of Lorwyn-Shadowmoor block and Lorwyn Eclipsed.

- Just-under-17-year span between Saviors of Kamigawa (May 2005) and Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty (February 2022)

- 11 years between Future Sight (April 2007) and Dominaria (April 2018)

- 10 years between Dragons of Tarkir (March 2015) and last year’s Tarkir Dragonstorm (April 2025).

Given those comparisons, it’s interesting that Lorwyn Eclipsed didn’t change more about the plane. Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty was almost a different world from its predecessor, dramatically overhauling its aesthetic and flinging it from the medieval to the future. Dominaria did something similar, salvaging the titular plane from its post-apocalyptic wreckage and synthesizing the history of its civilizations into a world reborn.

Chomping Changeling by Nils Hamm

Lorwyn Eclipsed is a tad different: it tweaks the particularities of the Lorwyn/Shadowmoor distinction, and its flavor makes abundant references to how the plane’s societies have changed since the Phyrexian Invasion of March of the Machine. But, this was not a world flung into the future or rescued from the abyss. It is, more or less, still itself. And for that very reason, the changes to Lorwyn’s visual language are all the more revealing.

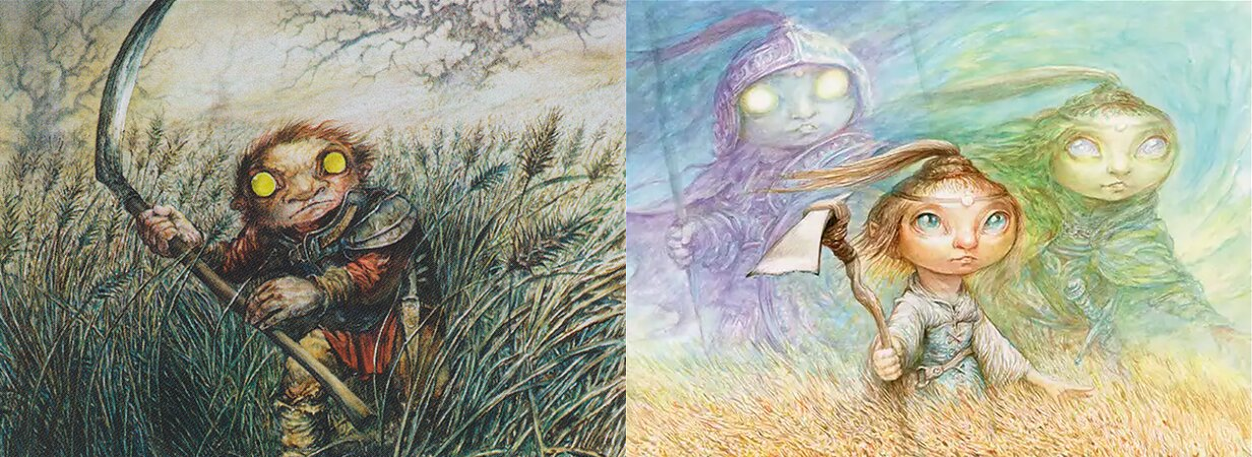

Mistmeadow Skulk and Figure of Fable by Omar Rayyan

These changes come into relief if we consider the 32 artists for Lorwyn Eclipsed who also worked on the original Lorwyn-Shadowmoor block. Critchlow and Alex Horley-Orlandelli are back; so are Omar Rayyan and Jeff Miracola; so are Richard Kane Ferguson, Steve Ellis, Scott M. Fischer, and many more.

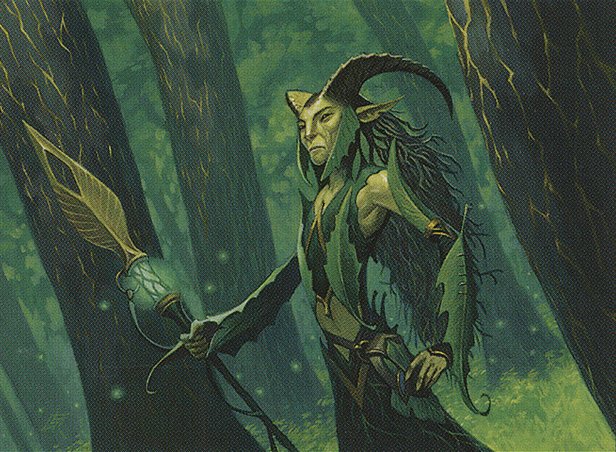

Gilt-Leaf Archdruid by Steve Prescott

Although I could devote an entire article to seeing how these artists reimagine Lorwyn, I think the most telling pair of images is Steve Prescott’s Gilt-Leaf Archdruid from Morningtide, and Maralen, Fey Ascendant from Eclipsed.

Gilt-Leaf Archdruid is characteristic of early Lorwyn art. The archdruid and the environment around him are mutual extensions, not just because of his leafy costuming but because he is a chromatic extension of the world. Green, especially yellow-green, is everywhere in this image; the archdruid’s complexion has the same pale verdancy as the grass and trees; even the trees crack with sappy yellow.

Although the environment is alive, it does not seem especially welcoming; matching the archdruid’s stern expression, the looming trees, and the hazy monochromatic background. This world seems intimidating, more than a little harsh.

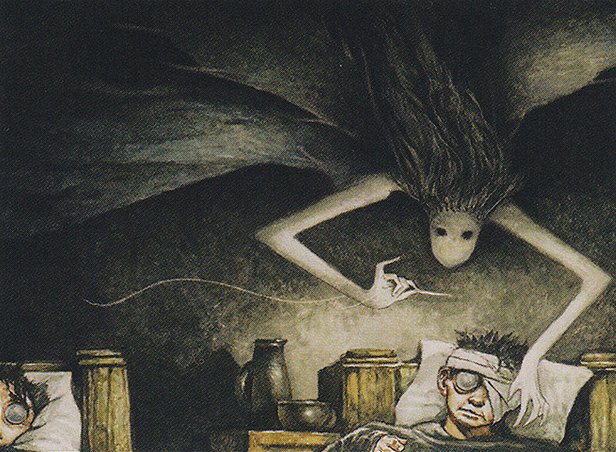

Suture Spirit by Larry MacDougall

This painting is comparatively tame compared to some of Lorwyn-Shadowmoor block’s grislier images, but you can still understand that this forest is part of the same eerie, threatening world as Blowfly Infestation (Drew Tucker), Suture Spirit (Larry MacDougal), and Sanity Grinding (Lars Grant-West).

Gilt-Leaf Archdruid is fairly representative of the original Lorwyn, in this sense. Although no Magic set is a monolith, Lorwyn-Shadowmoor block abounded in relatively unsaturated sepia tones, hazy backgrounds, and grim imagery. This world, as I perhaps intuited before I knew Lorwyn’s name, was resistant to your presence; like the xenophobic Gilt-Leaf elves, it is hostile to those looking in.

But in Lorwyn Eclipsed, that dynamic changes.

Maralen, Fae Ascendant by Steve Prescott

In Lorwyn Eclipsed Maralen, Fae Ascendant, Prescott does something radically different. Most striking, compared with the relatively desaturated monochrome of Prescott’s earlier painting, is the deep saturation and wide diversity of colors. The forest milieu is no longer steely green but aqua, against which golden fireflies and the pale brown trees and Maralen’s chartreuse complexion and her multicolored floral accoutrements all pop in vivacious tones. The painting’s darkest colors are darker than “Gilt-Leaf Archdruid”, but its brightest colors are brighter; the air of mystery has not disappeared, but it now pops with luminous life. Maralen’s expression, open but mysterious, confirms this effect.

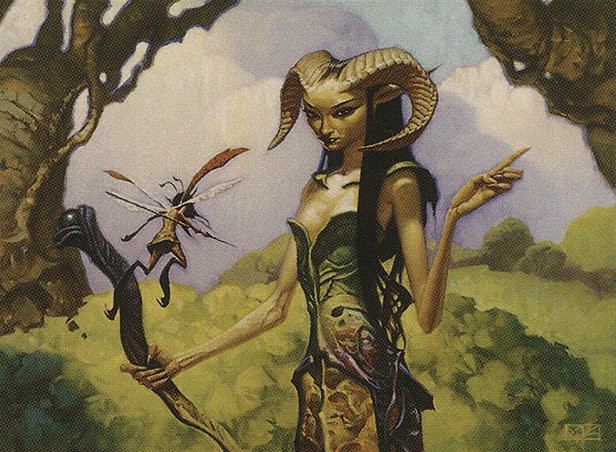

Maralen of the Morningsong by Mark Zug

Admittedly, this illustration is also in dialogue with other works from original Lorwyn block, like Adam Rex’s Oona, Queen of the Fae (part of Oona’s spirit inhabits Maralen’s body, which influences the latter’s flower costuming) and Mark Zug’s Maralen of the Mornsong (it is the same character, after all), but Prescott’s two paintings bear out the contrast between old and new Lorwyn. This world is not recalcitrant but inviting: what mysteries may lie here?

The effect is hammered home in another illustration from Lorwyn Eclipsed—one that, when paired with Prescott’s two images, tells us everything about how the plane’s aesthetic identity has changed.

Decadent Decay

Evyn Fong’s Dawnhand Eulogist is perhaps my favorite illustration from Lorwyn Eclipsed:

Dawnhand Eulogist by Evyn Fong

There are, on one hand, certain affinities between Dawnhand Eulogist and Prescott’s Gilt-Leaf Archdruid. Like Prescott’s Archdruid, Fong’s Eulogist is dominated by just a few colors–mostly purple and pink–and its central elven figure is set against a dark, ambiguous background. This is the visual-genetic material of Lorwyn, passed across the decades.

But Fong’s painting also displays the visual transformations we see in Prescott’s Maralen– and supercharges it. Its intensely saturated colors and its deep, contrasting shadows seem to explode out of the frame, like the bursting dawnglove flowers in the foreground. Although, as I suggested a moment ago, purple and pink are the dominant colors, Fong’s intense chromatics also draw the eye to other shades: the electric blue of the Eulogist’s gossamer shawl; the steely green speckling the petals on the image’s right side; the cerulean stems and lemon blossoms popping in every direction. In the background, hazy figures cradle flowers like etchings in a mystic image.

It is, in short, an intensely absorptive painting. Its decadence inhales, envelops, swallows (pick your metaphor) the viewer in saturated intensity. As I’ve written on my Substack Dominarian Plowshare, more than a few of Lorwyn Eclipsed’s illustrations are concerned with the condition of absorption, with the way that a viewer might, like Lewis Carroll’s Alice, tumble into a strange and different and unsettling other reality.

In this painting—if we’re to judge by the Eulogist’s powerful, melancholy expression, or indeed their very name—the process of absorption is somehow mournful.

At one level, this affect fits the painting’s subject: the Shadowmoor-native dawnglove flower is capable of staving off illness and even death, but the lachrymose Shadowmoor elves, with their intense love of natural beauty, refuse to pick it. To discover the flower is to have reached the end of all mortal suffering—but then to be paralyzed on the threshold, transfixed by beauty.

If Prescott’s earlier “Archdruid” embodies a world hostile to the viewer, and his “Maralen” is eagerly inviting, then Fong’s “Eulogist” helps us see that this invitation is also arcane and dangerous, soporific. This is the kind of decadent degeneration of which the Victorian poet Algernon Swinburne writes:

“Yea, though their alien kisses do me wrong,

Sweeter thy lips than mine with all their song;

Thy shoulders whiter than a fleece of white,

And flower-sweet fingers, good to bruise or bite

As honeycomb of the inmost honey-cells,

With almond-shaped and roseleaf-coloured shells

And blood like purple blossom at the tips

Quivering; and pain made perfect in thy lips

For my sake when I hurt thee; O that I

Durst crush thee out of life with love, and die,

Die of thy pain and my delight, and be

Mixed with thy blood and molten into thee!”

To view Fong’s painting is to be entranced by its world—and now you’re trapped in it, lulled into something like ecstatic annihilation.

Amor Fati

When I first entered into Magic, Lorwyn’s imagery, its colors, its very vibe, alienated me. It seemed to pervert my vocabulary, inundate me with grotesquerie, and claw back at my imagination when I tried to reach for it.

As I’ve learned, antipathy is what distinguishes Lorwyn among Magic sets: its harshness is not the overt horror of Phyrexia or Duskmourn, but rather something primeval and pedestrian and all the more haunting.

Liminal Hold by Ovidio Cartagena

At first blush, it might seem like Lorwyn Eclipsed neutralizes its negativity with bright colors and popping cinematic imagery. But, as we can see in Prescott’s and Fong’s elves, these transformations speak to the darkness that still pulses in the plane. The viewer might be invited into this decadent, beautiful world, but darkness lingers.

Ryan Carroll (he/him) is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English and Comparative Literature. Writing on Substack as Dominarian Plowshare, he thinks about Magic’s art, story, and experience. Outside of Magic, he writes on topics including 19th-century literature, information theory, television politics, and cliche.