It’s been more thrilling for me to pull lands from an Edge of Eternities pack than any other set I’ve played.

This isn’t just because of the high strategic and resale value sealed within booster boxes (though, in fairness, opening a foil shockland is nice).

It’s also because lands are doing something special in Edge of Eternities, something that stretches the grammar of Magic’s gameplay and the symbolic codes of its flavor.

That EOE is concerned with land is evident enough from the set’s factional flavor. The Red-aligned Kav are defined by the extractive destruction of their world, which has left them in a hostile conflict with the remnants of the planet Kavaron itself. The Green-aligned Eumidians represent the opposite. Springing from the lush world of Evendo, they seek to terraform the world and biomorph themselves in order to perfectly harmonize biology with the planetary.

But even more, land is the mechanical foundation of Magic, just as it’s the physical and psychic foundation of human life. Everything we do, are, can be, is bounded by the land on which we’re nestled. And EOE plays with this fact.

Moving to space demands we challenge our sense of what it actually means to make land the milieu of our lives. How do we conceive ourselves as belonging to space other than that on which our species evolved? How do we relate to physical features that seem to course with their own dynamic energies? And how does it feel to glimpse something so far beyond us that it even defies the name “land?”

To Boldly Go

One of the great concerns of the space opera genre is that of novelty—of how an audience relates to the unfamiliar world they’re seeing before them. Whether a story’s protagonist is a wide-eyed explorer or totally at home in their world, for a reader everything is foreign. Story is thus always a matter of negotiating our status as newcomers.

And this fact is especially true of landscape, considering that the very essence of the genre—space opera—is about transporting us beyond the physical confines of our world. We’re made to encounter physical spaces that are legible but radically challenging, unknown.

In various ways, EOE’s art attempts to deal with the issue of the unknown. In some cases, it manages the unknown through the feeling of discovery.

Breeding Pool by Chris Ostrowski

Take, for example, the “Viewport” style in which the set’s Mythic Legendary land cycle and shockland reprints are bedecked. The Viewport lands (illustrated by either Chris Ostrowski or Piotr Dura) jettison the traditional Magic card frame and render the top two-thirds of the card in sort of visual second-person. In each, we gaze over the shoulder of a figure who is, themselves, staring out of a ship’s viewport onto a planet.

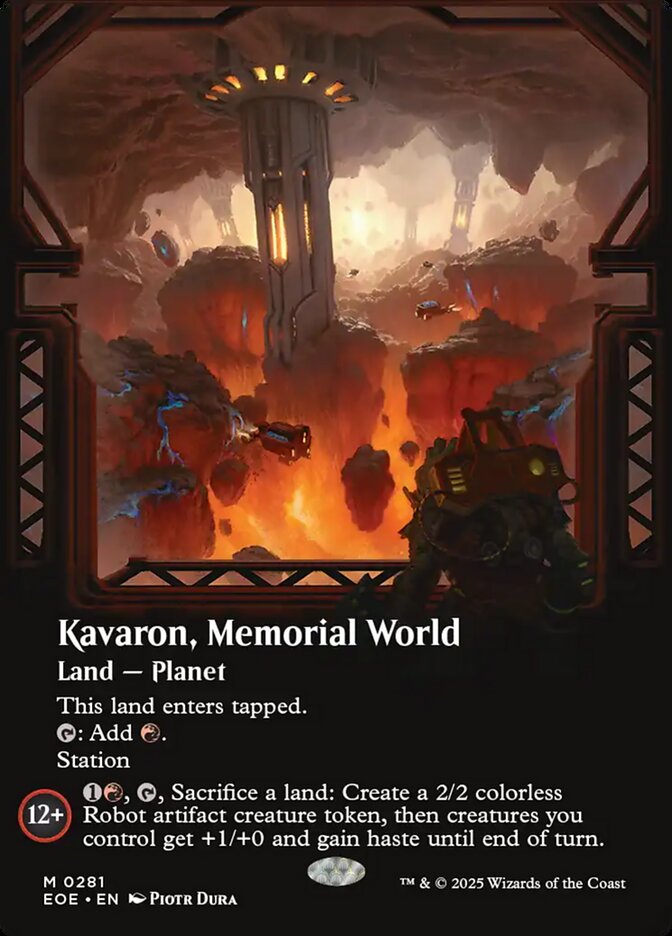

On Ostrowski’s Breeding Pool, we look on a Eumidian, who is itself watching its kin tromp down a catwalk and into a bubbling spring of ichorous liquid. Godless Shrine shows three Sunstar warriors, blades sizzling gold as they stare down at the immense monolith of a Monoist-held world. In Dura’s Kavaron, Memorial World, a silhouetted Kav peers down—one feels inclined to say melancholically—on the exploding caverns of his homeworld.

Kavaron, Memorial World by Piotr Dura

These illustrations relate us in a special way with the strange lands upon which we look. On one hand, we’re screened off from the scene, seeing it just over the subjects’ shoulders. Simultaneously, in the act of looking, we partake of the figures’ belonging; these lands are not foreign to these observers, after all, and by following their line of sight, we sink halfway into them.

Although we may be strangers, our position as a viewer is made secure. We are led to look upon this world like its inhabitants do, as one we might roam through, or mourn over, or fight for.

Infinity and Beyond

A similar operation happens in many of EOE’s “Poster Stellar Sights” lands, variant versions of classic speciality and utility lands. As its name suggests, the series was inspired by the aesthetic of travel posters, which first appeared in the mid-nineteenth century and further innovated by twentieth-century artists like Roger Broders, David Klein, and graphic designers in the New Deal Works Progress Administration.

Although such posters are stylistically diverse, they tend to feature stylized imagery, popping colors, and clean composition, melding the cool focus of design with the exuberance of exploration.

Like these posters, the “Stellar Sights” series works by making unknown lands feel vibrant, exciting. This is not the horror of the unknown but rather the vibrance of cool.

Mana Confluence by Matteo Bassini

This series contains some of my favorite art in the entire set. Sam Chivers’ Cascading Cataracts, which is soaked in a luminous blue-green glow and composed of undulating lines that stretch toward the horizon, renders both the mysterious beauty and the immense scale that is day-to-day in the Edge.

WFlemming Illustration’s Endless Sands shows a torrent of stardust blowing through space, surging toward or perhaps arriving from a distant body; whatever this event is, it has the arresting serenity of wind across a desert.

And the multicolored cumulus in Matteo Bassini’s Mana Confluence–my current phone wallpaper–visualizes the way that the force of magic vitalizes even a cracked, arid expanse.

In this sense, the “Poster Stellar Sights” series makes the expanses of space knowable to us by making them plainly beautiful. More than that, the snapshot style of travel posters—the way they seem to capture everyday moments of attractive lives–gives a delightful sense that, in these places, the extraordinary is entirely ordinary.

I also appreciate “Stellar Sights” because it tinkers with travel posters’ basic logics: commodity and possession.

We should appreciate the fact that traditional travel posters are mass market commodities. They were initially developed to market capitalist innovation, and now, being rebranded as retro cool, they market slivers of the past. They work by converting the intangible foreignness of another place (and, in some ways, of the future or the past) into something you can possess. I could never describe how France feels, but for just $20, a poster lets me stick the feeling up on my wall.

Magic cards are hardly free of commodity status, and to be sure, Booster Fun represents a kind of turbo commodification. But “Poster Stellar Sights” is nonetheless able to tweak old travel posters’ gleeful commercial aesthetics.

Bonders’ Enclave by BEMOCS

There’s a winking irony, for instance, in BEMOCS’ Bonders’ Enclave. Its visual language—blooming color, sharply lineated design—aestheticizes the far reaches of space, but the monstrous attack it so quaintly represents refuses domestication. BEMOCS’ blooming and smooth lines makes this illustration, and the land it imagines, something we want to have and hold—but its whimsical understated violence reminds us that possessing such unknown land is really a fiction.

Basically Impossible

Our little trip has thus far taken us through the way that speciality art treatments deal with the problem of land and the unknown, but Edge of Eternities’ treatment of land runs even deeper.

In fact, the set’s experimentation with land aesthetics happens at the most fundamental level of any Magic set—in the five cards that, before any set’s size is calculated or the colors apportioned or the flavor dreamt up, are sure to be present: the basic lands.

Plains by Sergey Glushakov

As with EOE on the whole, the art for the basic lands is stunning. But I’m especially struck by four illustrations in the suite of basic lands: Liiga Smilshkalne’s Island and Swamp and Sergey Glushakov’s Plains and Forest.

Smilshkalne’s and Glushakov’s lands are devoid of sentient presence (save for, perhaps, two stray ships tucked into the folds of Glushakov’s Forest). And in fact, they bear little resemblance to anything we might normally call “landscape.” They are immense cosmic bodies, rivers of light and pulses of energy and undead stars.

It strikes me that both Shilshkalne and Glushakov are in dialogue with astrophotography, the practice of developing images of celestial objects. Like their EOE basics, astrophotography keeps one foot in the sublime and one foot in the human.

Astrophotographs defy our sense of scale and expression. Nothing, we think, as we gaze on images like those taken by the James Webb Telescope, could exist on Earth. At the same time, their titles and framing attempt to reach vocabulary that might render them knowable, with names like “Cosmic Cliffs,” and “Pillars of Creation.” And yet still, what we see stubbornly defies our capacity to know it.

This truth is at the heart of astrophotography as a medium: because telescope cameras capture light differently than the human eye, and indeed because much of the action going on in space is invisible to the human eye, astrophotographs need to be meticulously edited in order to display the vibrant colors of celestial phenomena. What we see in astrophotographic images might be an approximation of what the eyes would see in deep space, or at other times a composite of light invisible to our human eyes, but regardless, they are not one-to-one.

Like such photos, Glushakov and Smilshkalne direct us to the very limits of our perception. They use a familiar category, land—ah, that familiar thing, swamps and plains and islands—to gesture to a force beyond human imagining.

Forest by Sergey Glushakov

Glushakov’s paintings place great emphasis on the whorling movements of celestial dust. His Plains looks to be something like a quasar, with the exploding light at the center cutting cruciform through curling tendrils of stardust. In his Forest, cliffs of emerald light whoosh inward, elongating and swaying, evoking talons, trees, a cloak—but defying any of those associations.

Island by Liiga Smilshkalne

Smilshkalne, for her part, pays attention to the explosive power of energy itself. As I’ve previously written on my Substack Dominarian Plowshare, Smilshkalne is distinct among Magic artists for her ability to represent what magical must feel like: the thrumming power at the heart of creation, the inescapable mystical force a mage must necessarily grasp in order to produce even the simplest supernatural effect.

Swamp by Liiga Smilshkalne

Her Island and Swamp find mystery in the sidereal, mystical force that evokes something we understand but also shatters our very understanding. Her Island is a nebular crown of stars, pinpricks of energy that seem to pour sapphire light down into the heart of being. This is nothing like a waterfall—and yet, and yet.

Smilshkalne’s Swamp is similarly impressive: purple-red stardust coalesces into cavelike swirls, in whose cavities roar the furnace of solar fire. At the base of this wall, sidereal power manifests as blooming lotuses, their energized petals drifting lazily away from their beaming white hearts. An earthly sight—and yet impossible.

Like astrophotographs, all these images us to recognize celestial phenomena as familiar—as land, analogous to the golden plains of Dominaria or oases of Amonkhet. Yet they make a mockery of such analogies.

Is that really a lotus, or some brilliant display of cosmic power? Is this nebula, a hundred millions times larger than my body, anything I could really call an island? If this is land, it’s land that exceeds my capacity to know it. My mind stretches to make it make sense; my spirit rhapsodizes as I fail.

Landfall

The sign of a great work is that it can change our way of inhabiting the world, the system of values and meanings that coordinate our embodied existence. And in turn, the sign of a great Magic set is that it can toy with the basic vocabulary through which the game inhabits us.

Based on these criteria, EOE is an exceptional set—in ways that, I think, we can discover in so many of the set’s nooks and crannies. It asks us to look under the hood of Magic as a conceptual system, to see the little pieces of meaning that make it whir—issues of incomprehension and faith and futurity and time, and here, what it means to belong to land.

How can I look at a blooming nebula or exploding planet and say “This is a Plains” or “This is a Mountain?” In fact, the set wants you to ask if you can.

Ryan Carroll (he/him) is a writer and Ph.D. candidate in English and Comparative Literature. On Substack as Dominarian Plowshare, he writes about Magic’s art, story, and experience. Outside of Magic, he writes on topics including 19th-century literature, information theory, television politics, and cliche.