As we gear up for two consecutive Innistrad preview seasons over the next two months, it’s worth taking a moment to appreciate the original Innistrad. That set might be one of the most influential sets for contemporary Magic design, from how it proved that top-down design could be successful, to how it changed the landscape of removal, to how it threaded the needle between open-ended archetypes and tight linear tribal decks. It’s also one of my favorite sets of all time, releasing just as I was hitting my stride after a ten year hiatus.

Making Top-Down Design Work

Ten years ago, there was no Theros, Amonkhet, or Eldraine. Magic sets drew inspiration from external sources, like Ravnica from Central Europe or Zendikar from Dungeons & Dragons, but they were exclusively bottom-up designs, structured first and foremost around mechanical themes. Magic had made few attempts at top-down worlds and the last one, Kamigawa, was seven years earlier and considered one of Magic’s weakest designs. Innistrad was a major experiment. Its success paved for the way for a decade with top-down designs, where even bottom-up worlds like Kaladesh, Ixalan, and Tarkir nevertheless were generally enhanced by their strong real world influences.

Reflecting on Innistrad, I’m surprised how much I loved the set’s thematics. I really dislike horror. I don’t enjoy being scared, I don’t watch scary movies, and I don’t play horror games (except for a lot of Left 4 Dead at the time). Yet despite not growing up with the source material, so much of it suffused the cultural zeitgeist in which I was raised that I felt like I got enough of the references to enjoy it. I hadn’t seen The Fly, Carrie, or any (non-Mel Brooks) take on Dr. Frankenstein, but I knew the tunes well enough to hum along.

The set was spooky without being scary, making it something I could still enjoy (and which Magic could still market to children). The set was a home run despite me not thinking it’d be for me. And the narrative succeeded in an era much like today, where its infrequent stories followed in the wake of panned precursors.

A Light and Weird Tribal Set

Tribal sets tend to foster rigid Limited formats. You pick a tribe and then your draft goes on rails. Each tribe values different things, so each tribe can often find what it needs and decks homogenize across drafts. Sure, your Lorwyn Merfolk deck might not always have Summon the School plus Drowner of Secrets, but almost all would use Silvergill Douser to lock up combat.

Innistrad loosened that paradigm in several ways. Tribes were only in allied colors, but each enemy color pair was supported (and usually used the graveyard in some way), so there were options beyond drafting a tribal deck. The tribes lacked usual cornerstones like Lords—cards like Diregraf Captain wouldn’t come until Dark Ascension.

But also, the tribes were kind of bad. WU Spirits had little mechanical cohesion or support, using some Flying-matters and token-matters. Vampires were weak, relying on cards like Bloodcrazed Neonate so high variance and frustrating that they’d never be printed today. Werewolves were cool, but that excitement stemmed from the introduction of double-faced cards—they had scant mechanical cohesion (and suffered from red’s low power level). Zombies were the worst of the bunch, as a blue-black zombies deck struggled to function when its blue zombies needed creature cards in the graveyard and black zombies centered around creature tokens. The only truly functional tribe was GW humans, which effectively told the story that humans needed to cooperate to survive in a world of monsters.

Somehow, it all worked. The tribes were weak enough that no heavy-handed glue like Changelings were necessary, but functional enough that you could draft them and win games. The set (mostly) had the right balance between power and synergy such that you needed varying amounts of each to succeed. Decks could be built in a variety of ways, dipping their toes in token, graveyard, tribal, Voltron (suit up one creature), or Aristocrats (sacrifice creatures for value, a term coined in this block) strategies. This made the format incredibly dynamic and replayable, where two same-colored decks decks could differ radically.

Mechanical Success and Repetition

Innistrad was a revolution in mechanical design. While double-faced cards are enormously successful, they were controversial in 2011. Now, transforming double-faced cards are Magic’s best way of communicating change. They’ve even spawned an entirely separate twist in Zendikar Rising’s modal double-faced cards.

Innistrad was the first non-Core Set to use newly-keyworded Hexproof. Hexproof would add the worst blemish on its Limited record, the frustrating and nigh-unkillable Invisible Stalker (who could wield a Butcher’s Cleaver or Silver-Inlaid Dagger with ludonarrative dissonant impunity). Prey Upon introduced Fight to the world and green would forevermore have access to strong common removal (and stopped getting regular random color pie breaks like Arachnus Web). Curses would quietly be used again and again, bringing a tiny bit of World Enchantments into the modern world. Innistrad also introduced the multicolor uncommon build-around that would immediately go on to be a hallmark of Limited design.

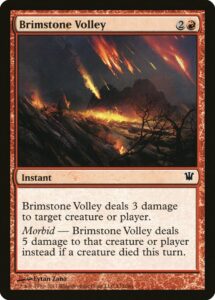

And then there’s Morbid. Death was already so valuable in Innistrad with WB aristocrats, blue Skaabs, and every color using the graveyard as a resource. Morbid took this foundation and created tension in every combat—players had to guess whether a chump attack was an attempt to enable Morbid or a bluff to sneak in damage. Innistrad’s removal was toned down to force combat to matter more in enabling Morbid, and it was awesome.

The problem is that after Innistrad, Magic continued to depress the power of common removal despite Morbid not creating tension in combat. This trend combined with the gradually increasing power of common creatures to yield formats like Kaladesh, Amonkhet, and Ixalan, where removal was so poor (and creatures so much better at attacking than blocking) that formats devolved in aggro races. So while I see Morbid’s effect on the set as part of its brilliance, I also see its success as ultimately damaging to Magic’s next five years.

A Question of Complexity

Reviewing Innistrad, I’m struck by how straightforward so many of its commons and uncommons are. Sure, there are little puzzles like finding all the ways to use Armor Skaab or Selfless Cathar, but it feels like Innistrad’s cards have a lot less text than Adventures in the Forgotten Realms’. At the time, New World Order (a design paradigm about reducing card complexity at common) was relatively recent and in full effect, while our post-Dominaria world intentionally has a fair degree more complexity.

I don’t mean to sound like an Old Fogey going on about how overly-wordy modern Magic cards are. Part of the reason that Innistrad cards were simple is that there was a lot to track between Flashback cards in graveyards, the looming dread of Morbid, and Werewolves’ constant transform triggers. That said, I can’t help but appreciate just how much utility was squeezed into Armored Skaab‘s single ability, the fact that Chapel Geist was playable despite being a French Vanilla with a barely-relevant creature type, and that Sticher’s Apprentice doesn’t have a second ability to just make a Homunculus for six or seven mana.

Massive Imbalance

While Innistrad is one of my favorite sets of all time, it’s impossible to look at it rose-tinted glasses and not be reminded of the glaring fact that red was bad. Sure, Burning Vengeance was awesome, but red had the worst creatures, the least functional tribal contributions (green got all the good werewolves and vampires mostly folded to an early blocker), was the worst at using its graveyard, and only had serviceable removal to show for it. This was still the era when much of red’s power was locked up in high variance cards like Furor of the Bitten and Vampire Neonate (though that era was coming to a close).

It’s good to remember the faults of a beloved format in addition to its many triumphs. It’s not possible to ship a perfect Magic set, but even the best set has its problems. There will basically always be a worst color, though ideally it’s not as bad as red in Innistrad or blue in AFR. I’m just a bit tickled that both Innistrad and Dominaria, two of the most revered sets of the past decade, both have this same issue.

Spider Spawning might be one of the most famous Limited archetypes of all time. Its existence is another accolade in a set deserving of many. The real beauty of the deck isn’t that it took over a month for people to figure it out, nor is it how powerful it is. Spider Spawning is amazing because it takes the least playable cards in the set and polishes that turd enough to make a dung beetle proud.

The secret to drafting it was discipline—you really only needed Spider Spawning, potent self-mill like Armored Skaab or Mulch, and 10-12 creatures. Sure, you could get fancy with Memory’s Journey plus Runic Repetition, but you didn’t have to. You would be punished for doing the normally right thing and taking the best commons like Dead Weight. The deck didn’t have room to dilute itself with things like removal or bombs when Gnaw to the Bone proved the most effective removal spell Limited had ever seen, and you only needed one copy.

It’s beautiful how much of the set supported subtly Spider Spawning without anyone noticing. While contemporary commons are almost all playable on rate alone, original Innistrad managed to make almost every common playable without it being as obvious.

Innistrad is the most important set to me. It released at a time of upheaval, where I didn’t know what I was supposed to be doing after college, had lost my way, and was finding a home for myself at Twenty Sided Store. It’s the first set I ever got good at drafting, the first set I streamed on Magic Online, the first set I played Standard with. It’s the set through which I made friendships that still last to this day. It’s the first time I really fell in love with an aggro deck—Travel Preparation was my jam. And that leads to the last card we’ll discuss today and my favorite combat trick of all time, Moment of Heroism.

While most tricks are about sneaking through lethal damage or converting combat into removal, Moment of Heroism adds a third dimension: tempo. As you likely know, lifegain for its own sake is awful but incidental lifegain is often outstanding. By stapling the ability to swing a race into your favor onto an unexciting combat trick, Moment of Heroism could be just as satisfying as “gain 10 life” as a removal spell—like on Gnaw to the Bone. The instances when benefited fully from both effects felt like you were truly getting away with murder, and I can’t imagine higher praise for a card from Innistrad.

And there’s our walk down memory lane. I’m looking forward to getting to visit Innistrad twice more in September and October. I find it amusing that it’s a major selling point for Magic to be returning to the classic Zendikar, Innistrad, and Dominaria we loved, while in the early 2010s, Magic upended every world’s characteristic point at the end of each block (and then spend the latter 2010s bring back their status quos).

It makes me wonder what the next several years of design will look like and just what the current paradigms of set creation are. How nostalgic will people be for Kaldheim, Strixhaven, and New Capenna after only experiencing them for one status quo-preserving set? What will a year of returning to Innistrad, Kamigawa, and Dominaria look like? How will Wizards effectively connect and distinguish two Innistrad sets releasing within two months of each other? I’m not sure, but as always, I’m happy to watch and get to play with all the new cards.

And, as always, thanks for reading.

Zachary Barash is a New York City-based game designer and the commissioner of Team Draft League. He designs for Kingdom Death: Monster, has a Game Design MFA from the NYU Game Center, and does freelance game design. When the stars align, he streams Magic (but the stars align way less often than he’d like).