The Brothers’ War standout Loran of the Third Path is part of a long legacy of cards that tracks back to Alliances’ Carrier Pigeons (or back to Legends’ Floral Spuzzem, if you squint). An abominable card by today’s standards, the Pigeons nevertheless set a precedent that would be explored in later sets: a creature with a positive effect when it enters the battlefield. This new innovation wouldn’t take long to become standardized: the Visions design team cribbed off the Portal team’s drafts of cards like Fire Imp and Serpent Assassin and, unlike Portal, made tournament-legal versions that came to define that period of Magic.

Overall, Visions was a salvo in the battle to make creatures matter. In the early years of Magic, the creatures that saw play were either mostly quick attackers—Savannah Lions, Order of the Ebon Hand, White Knight, etc.—or game-enders like Mahatmoti Djinn or Serra Angel. What we now call “midrange” creatures weren’t as powerful as these two classes—removal was powerful, and tapping three or four mana for a creature was a good way to lose tempo to a Swords to Plowshares or Terror. We may have lacked the sophisticated vocabulary to describe this tempo loss, but we knew the games when your Balduvian Horde bit the dust off a Dark Banishing were the ones you tended to lose.

The Visions/Portal team’s elegant idea to solve this quandary was to staple a one-time effect onto a reasonable body, so that even if your creature got removed immediately, you still got value. By our modern standards, these are weak, but Man-o’-War, Nekrataal, and Uktabi Orangutan were huge advances in creature technology and tournament staples at the time. Top tournament players and Magic philosophers were just starting to understand the concepts of “card advantage” and “tempo,” but when they were looping Uktabi Orangutan out of the graveyard with Recurring Nightmare, it sank in awfully quickly.

There was a perception, early on in Magic’s history, fair or not, that players were punished for wanting to play creatures—creatures often had serious drawbacks and were easy to clean up with Pyroclasm or Wrath of God, trading one card for multiple. By letting creatures effectively replace themselves, even if they were removed, whether directly through cards like Wall of Blossoms or by neutralizing an opponent’s card through effects like Cloudchaser Eagle, Wizards began rewarding players for running creatures. Cards like Gravedigger and Kavu Climber became Limited staples and important tools to help newer players understand the importance of card advantage, and the Visions vanguard started a trend that continues almost three decades later (and is only more powerful in the age of Panharmonicon and Conjurer’s Closet). Fire Imp may not be an impressive card twenty-five years later, but we wouldn’t have Fury without it and the precedent it set.

Initially, Wizards did not design these cards with “may” in their triggered abilities–in other words, if you played a Flametongue Kavu on an empty board, you’d be severely disappointed. While it rarely came up, Uktabi Orangutan/Viridian Shaman’s ability could be a drawback—without a “may” ability, you would have to target your own artifact if your opponent controlled none. By the time we hit the 2010’s, we were starting to transition to a “may” model–this did come with the drawback of potential missed triggers, but it also means the difference between a Flametongue or Skinrender binning itself or a Ravenous Chupacabra being able to be played on an empty board. Cards like Tin-Street Hooligan or Irreverent Revelers give you an out compared to Uktabi Orangutan and optional triggers like Manglehorn and Wild Celebrants are basically pure upgrade, also subtly balancing the “comes into play” model.

From the union of Uktabi Orangutan and Monk Realist, we got Reclamation Sage, the cleanest and most elegant Uktabi update yet. In exchange for a point of toughness compared to the Orangutan, the Sage gave us a relevant creature type and a crucial “may” in the triggered ability, which now targets both artifacts and enchantments. The Sage was reasonable, although underpowered for most environments. In Limited, it’s a fine card–you don’t always want a Disenchant but it becomes much more attractive when it’s a 2/1 that can snipe an Arrest or troublesome Equipment.

This was made especially clear in The Brothers’ War, where Disenchant was a necessary tool; if you were especially lucky, you could run Reclamation Sage 2.0 in Loran of the Third Path. Unlike Reclamation Sage, though, Loran has made the jump to Constructed, as an anti-Ossification cog that leaves behind a 2/1 with multiple other abilities. In the story of The Brothers’ War, as recounted in Jeff Grubb’s The Brothers’ War and the standalone “Loran’s Smile,” Loran is a native of Argive and one of the founders of the Third Path, a research organization that supported neither Mishra nor Urza in The Brothers’ War and prioritized magic over artifice. Betrayed by Gix and tortured by Ashnod, Loran reveals the secrets of the Golgothian Sylex to the sadistic artificier and survives the end of the War. She retires to a quiet homestead with Feldon, where she, weakened by her wounds and trauma, eventually dies. Feldon, in his grief, tries to recreate her as an automaton, an illusion, a revenant, and an idealized avatar, before realizing the futility of obsessing over the fragments of a once-complete person.

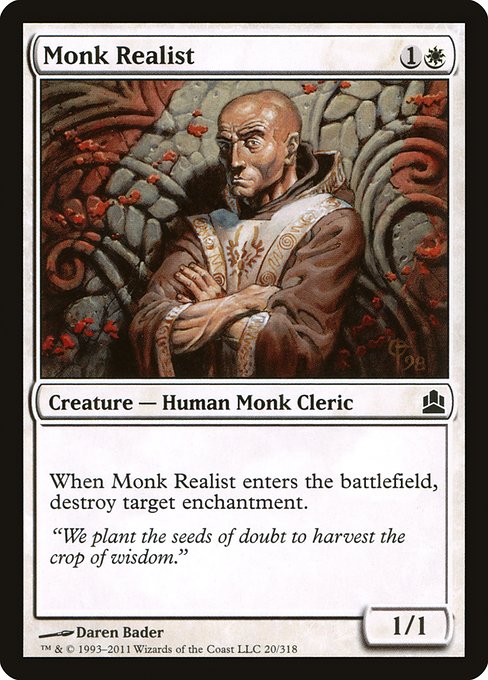

Loran’s enters-the-battlefield ability is a reflection of her mistrust of artifice and the importance of Disenchant in the era of Antiquities. It’s always amused me that disenchantment effects are either flavored as the surgical anti-thaumatic skill of a master wizard or the actions of a furious monkey–those adept at destroying magic artifacts or intangible auras are either Monk Realist or Rambunctious Mutt.

Loran is more of the Realist side of that dynamic, committed to finding ways to neutralize the destructive machines of the warring brothers and dedicated to sharing her knowledge, as reflected in her mutual draw ability. Wizards is experimenting with White getting shared card draw; Loran is a more surgical political tool than Secret Rendevous, offering you and your chosen opponent a single card. Loran’s tap ability is terrible outside of multiplayer games (and pretty suspect even then), of course, but it’s thematically appropriate coming from a charitable Archivist.

When the card was first revealed, I ignored it, assuming it would never come up. Instead, it’s been a minor but appealing part of the card—it comes into play as a last act of desperation, as I dig one card deeper during a fatal alpha strike to pull removal for my opponent’s Skitterbeam Battalion or lets me grind one more burst of advantage out of Loran as she throws herself in front of a Su-Chi Cave Guard. It symbolizes the war wearing on to a foregone conclusion–widespread destruction and the depletion of Dominaria’s natural resources–and the desperation of the Third Path as they search for any solution to the struggle between the titanic brothers. They ended the war, with Loran’s knowledge of the Golgothian Sylex triggering Urza to wipe the world clean of Mishra and his Phyrexian allies, but at phenomenal cost to the universe. You’d only offer your opponent a card under extreme duress, but at that point in the war, the Third Path was under the literal gun, Loran especially.

Ironically, Loran is great friends, gameplay-wise, with Elesh Norn, Mother of Machines and Sheoldred, the Apocalypse, but we can’t really fault her for choosing those allies in Standard. More suitably, she’s also great with her life and research partner, Feldon of the Third Path. Feldon can make simulacra of his dead lover, and you can exploit his pain to smash an artifact or enchantment every turn and even draw a card–just don’t think about the feedback loop of grief you’ve trapped him in.

That’s what Magic does best: iterate upon established archetypes to make more exciting cards and to tell stories in doing so. There’s a host of reasons why Reclamation Sage is a dime and Loran is a solid eight bucks, rarity, scarcity, and legality among them. But there are other, less tangible reasons: Loran is a character who tracks back two decades, and one with a tragic backstory. Her card draw ability is tantalizing, too, with the potential to start a story “so I was dead on board, but they were at four and I had a Sheoldred, the Apocalypse and a Loran out.”

As Magic design continues to develop, those emergent stories become the way we invest ourselves in the game, and the revisits to past eras builds a shared mythology. Loran, as a character, is crucial to the story of The Brothers’ War, but, as a card, she’s a crucial part of Magic’s design history–had she been represented in Antiquities, she never would have been as powerful or as intriguing, but after three decades of Uktabi Orangutan iterations, she’s come into her own, joining the ranks of Legends like Mangara, the Diplomat, Gix, Yawgmoth Praetor, and even her life’s love, Feldon of the Third Path. Diminished by war, separated by death, they’re now bound together again in dozens, if not hundreds, of Lorehold Commander decks.

Rob Bockman (he/him) is a native of South Carolina who has been playing Magic: the Gathering since Tempest block. A writer of fiction and stage plays, he loves the emergent comedy of Magic and the drama of high-level play. He’s been a Golgari player since before that had a name and is never happier than when he’s able to say “Overgrown Tomb into Thoughtseize,” no matter the format.