Cover art: Burning Fields by Yang Hong

This week, we summarize pages 48-85 of Roberts’ unabridged translation, roughly chapters 6-10. Still in the opening chapters, Luo tells us that the lack of a strong central authority is kindling for the fires of rebellion to reignite from the still-smoldering ashes of the Yellow Scarves Rebellion.

Read our other entries: Series Introduction; The Yellow Scarves Rebellion; Dong Zhuo Takes Control

Luoyang Razed (190 CE)

In the wake of Lü Bu’s defeat at Hulao Pass, Dong Zhuo is advised to take the emperor and move the capital west, upriver to Chang’an (present day Xi’an), which had been the capital two centuries before. The move to Chang’an can be read as an attempt as a legitimizing spiritual return, not to mention that in the face of opposition, Chang’an was better fortified by the natural mountainous landscape.

However, Dong Zhuo was short on funds and supplies, and needed some way of obtaining them. To create a thin veneer of cause, he ordered every rich householder with even a tenuous link to Yuan Shao and the rest of the coalition put to death, and their assets seized. Afterward, Dong Zhuo began the forced evacuation of Luoyang, a city housing millions, driving the populace before an army of 3,000. Luo tells us that “untold numbers” perished, and that while this happened, Dong Zhuo looted the crypts and temples of valuables buried with past emperors and empresses, forcibly evacuated the emperor, and ordered the city burned to the ground.

Cao Cao gave chase, but Yuan Shao hesitated; when Cao Cao’s army was beaten back, he blamed Yuan Shao in front of the entire coalition.

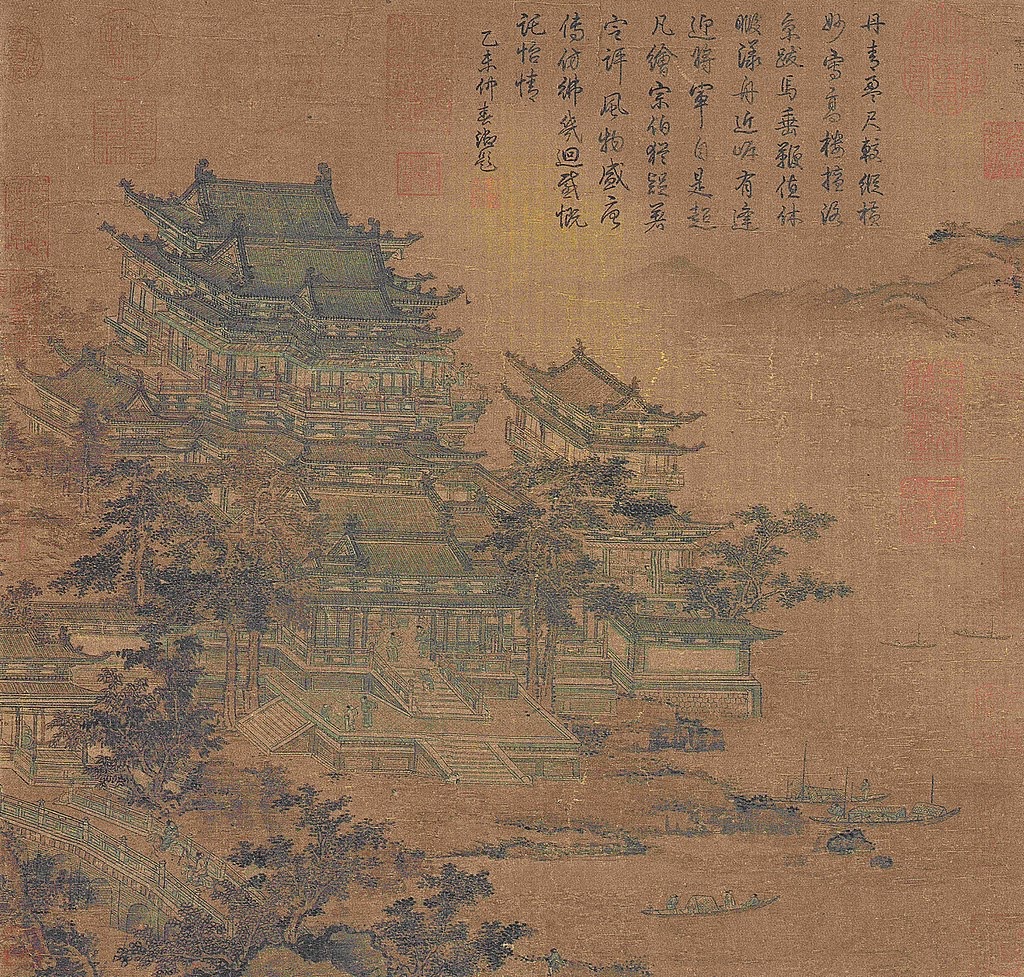

The Luoyang Pavilion by Li Zhaodao (675-758), ~500 years after the events described in this essay.

The Imperial Seal and the House of Sun (190-191 CE)

Yuan Shao’s forces moved into Luoyang and began clearing the rubble. One night, as the moon shone bright, Sun Jian, a powerful commander from the south, was weeping over the fate of the empire when he saw a rainbow-like light emanating from a well. In the well was the body of a lady of the palace, wearing a pouch around her neck. In the pouch was a jade seal, the top formed of five intertwined dragons — the Imperial Seal, which had been lost in the chaos of the assassination of the Ten. Sun Jian’s advisor, Cheng Pu, thought this a portent, telling him that “If Heaven has placed it in your hands, it means that the throne is destined to be yours.”

Thus, Sun Jian resolved to withdraw to his homeland, and plan his next moves from there. By the next day, however, word had come to Yuan Shao that Sun Jian had found the seal. When Sun Jian rode south, Yuan Shao ordered him intercepted, but no one could stop him.

Emboldened and desiring to rebuke Yuan Shao, Sun Jian and his son, Sun Ce, gathered troops and sailed up the river Han to lay siege to the city of Xiangyang. Despite a series of victories on the river and a successful siege, Sun Jian was caught by surprise and killed, his body taken by the forces of Xiangyang. For custody of his father’s body, Sun Ce negotiated a prisoner exchange and withdrew to the plains of Qu’e before riding to Jiangdu [just outside of present-day Shanghai]. His humility and generosity there attracted many to his service.

Portrait of Sun Jian from a Qing Dynasty manuscript.

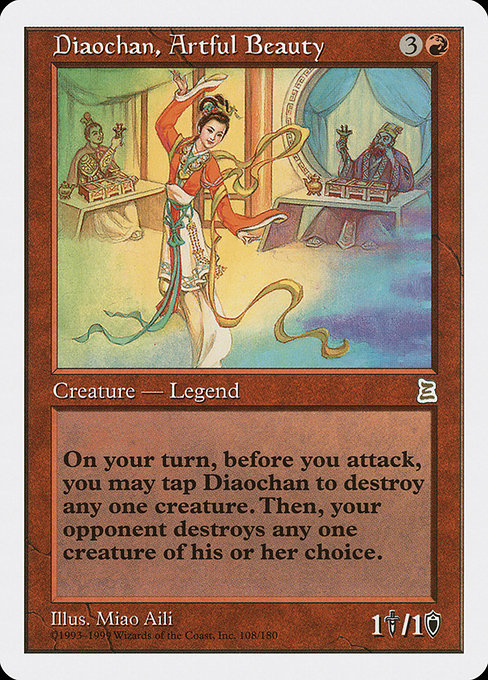

Diaochan (192 CE)

At Chang’an, Dong Zhuo continued his despotic control of the emperor and his resources. Wang Yun, whose blade Cao Cao had used in his attempt to assassinate Dong Zhuo, still served the empire, and grew despondent. Wang Yun had an adopted daughter, a talented singer and dancer named Diaochan, who saw this and felt deep sadness for her foster father. Out of a deep sense of duty to Wang Yun, Diaochan agreed to a plan in which she would be promised in marriage to Lü Bu, then offered to Dong Zhuo, pitting them against one another and inciting the brash Lü Bu to slay Dong Zhuo.

Lü Bu was easily wooed by Diaochan’s beauty, and on a subsequent night, Dong Zhuo too was entranced, taking Diaochan to the palace that very night. Lü Bu burned with jealousy, and the relationship between him and his adopted father began to crumble. Diaochan continued to play her role, confessing her true love to Lü Bu one moment, and professing her fidelity to Dong Zhuo the next, convincing each that the other was an abusive brute. Sending her away to his estate at Mei (west of the capital, along the Wei river) to avoid further conflict, Dong Zhuo attempted to mend his relationship with his adopted son; but Wang Yun interfered, convincing Lü Bu that Dioachan had been violated and Lü Bu disgraced by Dong’s insult. Infuriated, Lü Bu hatched a plan with Wang Yun, gathered loyal warriors, and killed Dong Zhuo, leaving his corpse burning in the streets for days on end.

Lü Bu took Diaochan into his care, but back at Chang’an, Wang Yun denied amnesty to four former generals who served under Dong Zhuo, and they were provoked to muster Dong’s remaining forces and storm the new capital. Wang Yun and his clan were killed, and the emperor was again at the mercy of power-hungry warlords.

The translator of the edition the Portal Three Kingdoms text is taken from, Moss Roberts, holds up Diaochan as the character he most admires: Diaochan accomplishes her mission in service to her family and to the dynasty, accomplishing through guile what the heroes of the novel could not achieve through might just a chapter prior. Based very loosely on an unnamed historical courtesan, and drawing more from the dramas of Yuan theatre five centuries after the Three Kingdoms period, Diaochan exists in the narrative as a foil that calls into question the achievements of the heroes.

Rebellion Begets Rebellion (193 CE)

The rise of Dong Zhuo’s loyalists undermines the power of Emperor Xian. Narratively, Luo signals that the lack of a strong central authority weakens the empire: rebellion begets rebellion. A new faction of Yellow Scarves Rebels, led by the last living brother of Zhang Jue, rises up in the east.

Cao Cao, having marshalled his strength in Yan Province, puts down the uprising, and coerces many of the rebels to surrender to the lord of Xuzhou, Tao Qian, and join his forces. It was these forces that Tao Qian employed to escort Cao Cao’s father (Cao Song) as he journeyed to rejoin his son in Yan Province. Seeing the immense wealth of the Cao caravan, the former rebels grumbled among themselves, conspired, and slew Cao Song.

Cao Cao is—as one might expect—sorely grieved. Because these troops had been under the authority of Tao Qian, Cao Cao was infuriated. In the span of a few paragraphs, we see Cao’s rhetoric move from “he allowed his men to kill my father!” to “[he] slew my whole family!” Vowing to take his vengeance against Tao Qian and the people of Xuzhou, Cao Cao rode with his forces to the province, massacring the populace and despoiling graves.

Faced with certain defeat, Tao Qian turns to the governor of Beihai county, in Qing province, Kong Rong. (Aside: To this day, Kong is known as a notable ancient Chinese author.) However, Kong himself was under siege by another army of Yellow Scarves Rebels numbering in the tens of thousands. When all seemed lost, the warrior Taishi Ci broke in and out of the siege to assess need and then to seek help from a heroic neighbor, known for “humanity and honor, and . . . willingness to aid people in distress,” Liu Bei.

What Was Not in the Cards

Instead of amending any old designs this week, let’s mull what sorts of cards we might add to “fill out” P3K were we to imagine it as a standalone, draftable set or cube. The narrative arc this week tells of Dong Zhuo’s continued tyranny and downfall. Dong Zhuo cares little for the Emperor and his shrines, and thus, were I to expand this set, I would add the card Faithless Looting. Given the pillaging and razing of the city, we may also consider Past in Flames, and cards that reference pillaging and plunder: Pillaging Horde, Pillage, Heartless Pillage, and Costly Plunder are great thematic additions.

“The Warrior and the Beauty” by Hao Wang Cao (好望草), my pick for a P3K Cathartic Reunion.

Cathartic Reunion is another card that may fit well here, and we can imagine such a reunion taking place between Diaochan and Lü Bu after Dong Zhuo’s downfall, along the lines of ancient Yuan operas, as well as dramatization in fanart and popular media.

Scene from the 1958 Hong Kong Romance, “Diao Chan,” starring Lin Dai.

Beyond these, I did not design them, but Kong Rong is historically significant enough to merit his own card, I’d wager; the same is true for Taishi Ci. This week, I do have one design, an attempt at a Saga, to amplify later with a “historic matters” theme. Dong Zhuo’s razing of a city under his control is an example of scorched-earth warfare, but also consistent with his previous pillaging of the people to enrich himself. The stages of this saga recall the execution of the rich for their wealth, the plunder of the imperial crypts, the burning of the city so it could not be used by the approaching armies of Yuan Shao’s confederation, and the establishment of a new capital at Chang’an.

In a casual Rakdos or Mardu Aristocrats build, where death triggers can offer even more benefits, The Razing of Luoyang has a lot of potential. It also has a fairly low floor—it requires resources to produce resources, and is slow enough, as a saga, to allow decisive warlords (not Yuan Shao, the Indecisive) to intervene with Tormod’s Crypt or Disenchant before Dong Zhuo concludes his plunder and escapes with Emperor Xian!

My friend Kristen mentioned that this design feels “Mardu,” and my editor Carrie noted that within the remastered cube or limited environment, some more support for “aristocrats” might be necessary for this to really be worthwhile. In that vein, let’s consider Hunted Witness, General’s Enforcer, and Bastion of Remembrance for our expanded set list. Anointed Procession, Attrition, Grave Pact, and Proper Burial are also on my list of possibilities for supporting this archetype in a potential P3K cube.

What do you think of this design? What cards would you add to the set in a P3K cube to support this archetype or represent these chapters of the story? Let me know on Twitter!

Read On!

The five chapters summarized this week leave Emperor Xian in a precarious position: freed from the despotism of Dong Zhuo, the new capital of Chang’an now falls under the control of Dong’s loyalists. What will become of the Emperor? What happens to Lü Bu and Dioachan? Can Liu Bei save Kong Rong from Yellow Scarves Rebels and save Tao Qian from Cao Cao? Find out next week in “The Fall of the Han Dynasty Part 4: The Rise of Cao Cao!”

Recommended reading:

Luo Guanzhong,Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel (unabridged), trans. Moss Roberts (Berkeley: UC Press, 1991), Chapters 6-10.

Jacob Torbeck is a researcher and instructor of theology and ethics. He hails from Chicago, IL, and loves playing Commander and pre-modern cubes.